The techniques and materials used to make cave paintings and other forms of rock art are almost as diverse as the people who created them. What unites these ancient artists – across almost all of the earth’s continents and over tens of thousands of years of ancient history – is their increasing level of incredible ingenuity.

Handy Work

The phrase ‘cave paintings’ somewhat obscures the vast range of methods used to create works of non-portable art on rocks and cave walls. They could be painted, but they could also be drawn, daubed, scratched, chipped, sculpted in relief, engraved, stenciled or even thrown on in some instances. They basically prove that practically all of the fundamentals of modern graphic art, short perhaps of freezing sharks in formaldehyde, were pioneered as early as 35,000 years ago or longer.

Quite naturally, ancient man started out with his fingers, either to mould and reshape the soft surface clay that could be found on the walls of caves, or to primitively apply pigment mixes. He probably then progressed onto using brushes made from animal hair, crushed twigs or pads of fur or moss (this is all based on pure speculation and modern experiments, since none of these tools have survived). Spray painting techniques even appear to have been used in some cases, by mixing pigment with water and spraying it either directly from their mouths or through tubes made out of animal bones, bamboo or reeds (Australian aboriginals still use this method today).

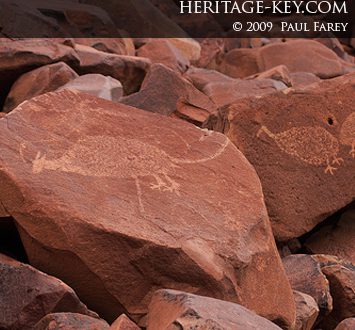

Carvings were cut or scraped into the surface of walls using anything from crude picks to sharp flakes of a type of rock called chert. Sometimes they would create whole elaborate standalone images. Alternatively, they would use carving as a means of augmenting painted lines, knowing that the light (usually from flaming torches) would reflect off of the differnent angles.

Most drawings were just basic outlines, but two of the finest examples of Paleolithic cave art demonstrate some quite advanced methods of infilling and detail. The amazing monochrome images of fierce predator mammals in Chauvet Cave, southern France, show a remarkably elegant grasp of shading, while at Altamira cave in northern Spain, there are examples of two-colour and multicolour figures, such as a stunning bison on the ceiling. No wonder it’s been called the “Sistine Chapel of Paleolithic Art”.

Bright Ideas

Not all cave paintings show use of colour, but those that do can be quite striking in the range and depth of their tints. Images at Lascaux, France, for example, comprise earthy browns and yellows, while the stenciled handprints at Cuevas de las Manos in Argentina exist in various brilliant oranges and reds. How was this possible, considering that the opening of the first art supplies store was still at least a few millennia off?

The range of colours Paleolithic man found in the natural world is quite remarkable – reds in the form of iron ore, blacks in the form of charcoal or manganese, yellows from iron oxide and whites from chalk or even burned bone or shell. Clay ochre too provided some basic colours. The artists displayed incredible ingenuity in applying these pigments to their pictures. At Lascaux, for instance, hundreds of rudimentary pigment crayons were discovered scattered around the floor. Analysis of some of these has revealed that artists used recipes to prepare them, combining the raw colour with talc or feldspar to increase their bulk, and adding animal and plant oils to bind the materials.

As already mentioned, clay could be used to mould images onto walls – one such example, of a three-dimensional bear at the cave of Montespan in France, was formed out of a whopping 700 kg of the stuff. Sometimes the natural contours and features of a cave, rock or wall – stalagmites or other mineral formations – would be used to accentuate and augment images (most often animals’ genitals).

A stunning cave painting from Altamira Cave in northern Spain. The detail, colour, scale and remarkable preservation of the images at this site is breathtaking.

No Cave Too Deep, No Ceiling Too High

It’s not clear what made ancient man single out particular caves and surfaces as suitable places to display their masterpieces. But certainly they didn’t always choose them for their accessibility.

To view some of the images at Altamira it’s necessary to squeeze into tiny nooks and crannies barely large enough for a child. At Cuevas de las Manos, the ceiling of the cave is covered in hundreds of coloured dots – experts have speculated that they were made by the artists submerging their hunting boleadoras in ink and throwing them up.

At Lascaux, where some images are up to 16 feet tall, the Paleolithic painters had a better idea. Holes in the cave walls suggest that in order to paint the higher parts they may have erected a rudimentary scaffold (from which we can also guess they wolf-whistled at any passing pre-historic ladies). The Astuvansalmi rock paintings in Finland were the consequence of ancient Scandinavians taking it upon themselves to apply their paintings to a sheer cliff face above lake Saimaa. Since the water level was higher at the time, they must have had to stand on a boat every day to create them. How’s that for dedication?

Painstaking Painting

If you thought that Michelangelo showed immense patience in taking four years to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome, then spare a thought for his Paleolithic predecessors. Recent research at Altamira in northern Spain by Dr Alistair Pike of Bristol University, England, has concluded that many of the great cave paintings in the world may not have been completed as a single endeavor, but as part of a long process that saw each added to, refreshed and painted over by generation after generation. Speaking to The Telegraph newspaper, Dr Pike said: “We have found that most of these caves were not painted in one go, but the painting spanned up to 20,000 years.” Talk about suffering for your art.