Charging In

In the 1830’s British colonel Howard Vyse explored the s of Khufu and Menkaure using a rather destructive method – dynamite. The colonel, along with John Perring, an engineer, blasted his way into four stress-relieving chambers in Khufu’s s. As the name suggests the chambers were built for engineering reasons and the colonel didn’t find any objects. He did, however, find some ancient graffiti saying, according to John Romer’s book, The Great : Ancient Egypt Revisited, “Khufu is pure! Khufu is bright!” And “May the White Crown of Khufu strengthen the sailing!”

They had more luck in Menkaure’s . Again using dynamite they blasted into the ancient pharoah’s burial chamber where they found a blue basalt sarcophagus, without a mummy. According a 2008 Times report Vyse wrote in his diary that, “as the sarcophagus would have been destroyed had it remained in the … I resolved to send it to the British Museum.” Ironically, the merchant ship carrying it to Britain sank off the coast of Spain.

Today, Vyse and Perring would be facing many years in an Egyptian jail for these actions. But back in the 19th century and into the 20th there were numerous instances where antiquarians, explorers and political rulers conducted activities that today would be seen as, at best, gross violations of antiquities laws.

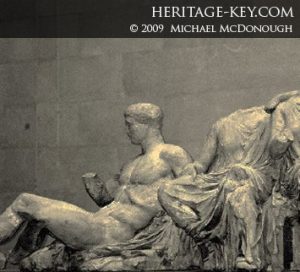

Lord Elgin used saws to hack off the famous Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon to move them to Britain. Giovanni Belzoni, in the early 19th century, took more artifacts from Egypt than Napoleon’s armies did, according to Brian Fagan in his book The Rape of the Nile. In 1937 the Obelisk of Axum, a 4th century A.D. monument created by the Kingdom of Aksum in Ethiopia, was taken to Rome by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, after his forces conquered the country.

Today most governments have laws that prevent these activities from taking place. To keep artifacts from leaving their country, and encourage their return, governments have designed antiquities laws to curtail exports and regulate the way archaeology is done. It is also common now for governments to ask foreign museums to repatriate artifacts that have already been taken.

Keeping it Legal

Today China, and countries around the Mediterranean basin such as Greece and Egypt, have strict laws on how archaeology is done and antiquities are handled. In these countries artifacts cannot be exported from the country without special permission – something that is rarely given. Digs must be approved and monitored by a government authority, such as the Supreme Council for Antiquities (SCA) in Egypt, which is headed up by Zahi Hawass. The people who conduct digs or investigations much have the proper qualifications, such as a PhD in archaeology. They must also report their findings to the state and turn over artifacts that are found.

Some countries, such as Jordan, allow artifacts to be temporarily brought out of the country for further scientific investigation such as ceramic analysis. Again this privilege is controlled and monitored by an official authority.

China and Greece allow citizens to import their country’s antiquities back in, but not out. This means that a Chinese citizen, with a Ming era artifact, can import it back into China without penalty. However if they are departing from China they cannot take the artifact with them, without special permission. These policies are written to encourage the return of antiquities that are now abroad.

Finders, Not Keepers

In their laws China, Greece and Egypt also make clear that artifacts found at a dig site are property of the state, regardless of whether they were found on private property. This means that a Chinese homeowner who finds Zhou era Spade money in their backyard cannot legally “own it,” so to speak – it belongs to the government.

British and the American cultural laws follow the same principles although they have been criticized for being somewhat more lax on the import-export of artifacts compared to the laws of China and Greece. A private property owner may also be able to make a claim to certain artifacts that are found on their land.

To curtail illegal activities the UNESCO Convention on the mean of prohibiting and preventing illicit, import, export and transfer of cultural property, bans illegal transfer of artifacts between states. So far 103 countries have ratified it, including Britain, Italy, Greece, China and the United States.

Modern Day Ethics

Even with the absence of antiquity laws archaeologists are encouraged to follow certain ethical beliefs: record site diligently, report all findings, publish as much as possible, don’t sell or steal artifacts, don’t publicly release information that will help looters, and so on. These are all principles that are taught in archaeology schools from Cambridge to Tokyo. Any student today who suggests dynamite as an excavation method would likely get a failing grade.

Museums also have codes of ethics, this is a basic international one, that prohibit accepting artifacts that are known to be recently stolen. They may also place restrictions on their staff identifying artifacts with an unknown or questionable provenience.

Callback

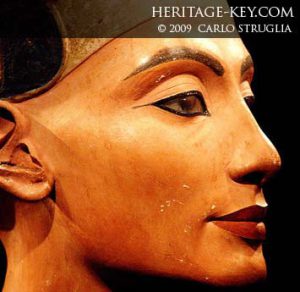

There are numerous attempts by countries to reclaim artifacts that were taken out in earlier times. Greece wants the Elgin Marbles back, Ethiopia got the Obelisk of Axum back in 2005 and Egypt wants several of its treasures back including the Rosetta Stone and the bust of Nefertiti.

This is only the tip of the iceberg of requests to return antiquities. There are several arguments made for repatriating arguments. Sometimes there is a legal argument, for example the seizure of the Obelisk of Axum was plain thievery by a fascist leader. Or the argument may be ethical; even in cases where permission was granted, sometimes it was by a government that was not representative of the people. For example, permission for the removal of the Elgin Marbles was granted by the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, who forcibly ruled over Greece at the time.

Aguably the strongest argument is nationalistic; antiquities are the property of the people of the country of origin and should be recallable by the state. James Cuno disagrees with that argument. He is president of the Art Institute of Chicago and says in his book, Who Owns Antiquity, that artifacts, “are the cultural property of all humankind… evidence of the world’s ancient past and not that of a particular modern nation, they comprise antiquity, and antiquity knows no borders.”

Arguments against voluntary repatriation vary from case to case, but often include concerns about the ability of a country, requesting repatriation, to properly conserve a sensitive artifact. The creation of the GEM museum in Egypt, with modern conservation facilities, helps to annul this concern in that country.

Other arguments include claims that permission was granted by the proper authority, as is occasionally put forward by opponents to the return of the Elgin Marbles, and the general claim that if every museum repatriated all their artifacts they would have little left to exhibit.

The priceless artefacts of antiquity may have been taken recklessly in the first instance, but their repatriation, if at all, will be a hotly-debated and lengthy process.