This Saturday throngs of visitors from across North America will head to the Royal Ontario Museum, the crown jewel of Canada’s cultural scene, to see one of the most important, and mysterious, texts in antiquity, the Dead Sea Scrolls.

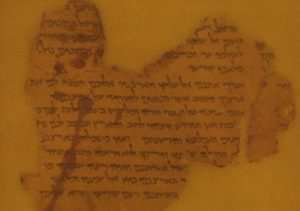

Dead Sea Scrolls: Words that Changed the World features fragments from Genesis, Daniel, The Book of War, Psalms, Daniel and the Messianic Apocalypse.

It also features artefacts from the site they were found (Qumran), as well as Jewish artefacts from Jerusalem and Sepphoris.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in 1947 by a group of Bedouins, said to be searching for a stray goat. They form the earliest known texts of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and date from the 2nd century B.C. – 1st century A.D.

As such they have given Jewish, Christian and Muslim scholars an opportunity to explore some of the earliest stories of their faith. An undertaking that, to say the least, has entailed no shortage of controversy.

Scholars hotly dispute who wrote them, how they came to Qumran and the implications they have for theology. An arrest earlier this year illustrates how extreme these debates can get.

Battle of the Scrolls

The ownership of the scrolls is disputed. Qumran is actually in the West Bank, a territory under the jurisdiction of Mahmoud Abbas’ fledgling Palestinian Authority. However, the scrolls used in the Toronto exhibit are owned by Israel – a sticking point with the Palestinians. Before they were even put on display the Authority’s leaders were demanding that Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper call off the show.

Harper, and the museum, refused.

So how does Canada’s largest museum present items of such great religious importance and controversy?

Answer: with great politeness.

Curating From the Fence

The exhibit takes pains to avoid bias towards any of the duelling theories. In fact it sticks so close to the few agreed facts that it offers little information as to the various competing ideas of how the scrolls came to be.

One of the first things a visitor sees after walking into the gallery is a three foot tall ceramic canister from Qumran. It is surrounded by a floor to ceiling wall with large questions written on it.

Who concealed the scroll? Why do the scrolls refer to a seemingly unusual form of Judaism? Who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls? Were the scrolls part of an ancient collection? If so whose? The exhibition is more full of questions than answers.

You start off by going through a gallery full of artefacts from the site of Sepphoris. The city had a large Jewish population at the time the scrolls were written. Incense shovels, lamps, ossuaries and ceramics give a sense of the devotional, but fairly modest, lifestyle of its inhabitants.

Left to the Imagination

Next you come to artefacts from Jerusalem and nearby areas, during the time of Roman rule. This was a period marked by rebellion and war. Tiles, manufactured in the city by its inhabitants, bear the mark of the Roman “tenth legion of the sea strait.” A set of arrowheads is displayed, left over from a 2,000 year old battle on the Golan Heights.

Qumran, the site of the Dead Sea Scrolls, is the next stop. The gallery exhibits a mix of items from the site including

jugs, funnels, bowls, a net, coins, scroll wrapping and even dried dates.

A sign has a list of ideas about the original purpose of the Qumran site (pottery production centre, monastic site, military outpost etc). But the exhibit doesn’t make a concerted attempt to flesh out these theories, much less take sides in the dispute.

The Essenes, whom many believe wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, are not featured in a large way.

No Pictures!

Finally you reach the scrolls themselves – they are housed in climate controlled displays. You will not get an opportunity to take pictures of them because of their fragility (selected media were permitted to take pictures for only one day). Again, the museum sticks to the agreed facts: what the texts say in translated verse, where they were found, and their timeframe.

And that sums up the exhibit. A lot of well-researched facts, many artefacts and a chance to the see the first known copy of the most well read book in the western world. But, if you’re looking for the big ideas on how the pieces fit together you’ll have to find a good book on the topic. Or perhaps some of the lectures surrounding this event will pack more of a controversial punch.