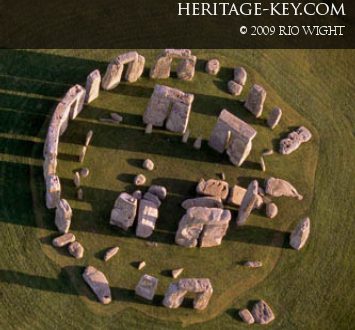

Stonehenge may have a history spanning almost 5,000 years, but the last century has been one of its most poignant and fascinating, seeing it restored from its former dilapidated state into one of Britain’s officially most loved tourist sites.

An Auspicious Start

Before 1901 Stonehenge was in a bad way. Many of the huge stones had sunk out of position; some had fallen over; and much of the land around the monument had been excavated beyond recognition. Seemingly every scholar who wanted to make a name for himself would visit Stonehenge for some reason or another. Even Charles Darwin commented on the area’s archaeological remains for his book The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms.

Stonehenge was, to put it mildly, a British treasure in a real mess. And its predicament came to the fore at the turn of the 20th century, when sarsen stone number 22 fell from its position and took a lintel with it. A public outcry at Stonehenge’s desertion, twinned with media pressure from the famed archaeologist Sir William Flinders Petrie, led to the government taking action to find someone who could restore the ailing monument to its past glory. Up stepped the famous engineer and ‘father of Japanese archaeology’ William Gowland, who attempted to straighten sarsen stone number 56 and set it into its original position with concrete. Gowland made some of the best archaeological discoveries around the earthen bed of Stonehenge whilst moving the monoliths; concluding that antler picks had been used to shape the stones whilst already in place – by virtue of hundreds of chippings under the soil.

Enthusiasm Gathers Pace

However Gowland made an error in restoring stone 56, by placing it half a metre away from its original position. As had many British dolmen and megalithic sites before, Stonehenge was the victim of a shoddy archaeological project. Yet Gowland’s dig, and the resurgence of Egyptology with Howard Carter’s groundbreaking discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, reinvigorated the British public’s enthusiasm for their own ancient treasures. And in the late 1920s there was an outcry against the number of modern buildings being erected around the site, such as an aerodrome built for the war. An appeal for money to buy back the area resulted in its ownership by the National Trust, who have since maintained its relative purity and added facilities such as a visitor centre, security and admission prices. This has helped the maintenance of the site immensely.

Another excavation project was soon undertaken, this time by Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley, who excavated the foundations of six stones undergoing restoration, finding a bottle of port which had been left by the 19th century archaeologist William Cunnington upon his work on the site. Hawley also worked on the ditch surrounding Stonehenge; concluding that there was once a moat which took water from an inlet to the northwest, round the monument to an outlet in the east.

Later work in the 1940s and 50s added to Hawley’s findings, discovering axes and daggers at the site. More was understood about Stonehenge’s construction and history, and many more excavations and restorations would be carried out during the 50s, 60s and 70s – setting yet more fallen stones and discovering more tools and archaeological evidence. A car park, built in 1966 to cater for the British public’s newfound adoration for Stonehenge, allowed scholars to dig up Mesolithic potholes dating back to between 8,000 and 7,000 BC. And a 1978 project by Richard Atkinson revealed the remains of a Bronze Age man, named the Stonehenge Archer, who was roughly contemporary of the henge.

Later Projects and the Riverside

Following the 1980s Stonehenge Environs Project, in which writer and archaeologist Julian Richards extensively surveyed the immediate locality of Stonehenge, there was a lull in interest in the monument. Yet the period of admiration was yet to diminish, and in 1986 the site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In a 2002 survey to find the Seven Wonders of Britain, to run concurrently with the New7Wonders mission, Stonehenge was placed firmly amongst the nations favourite places. The full list included the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben; Windsor Castle; the Eden Project; York Minster; Hadrian’s Wall and the London Eye.

In 2003 five British universities collaborated on the Stonehenge Riverside Project; an initial five-year discipline which ‘attempts to unravel the development of the prehistoric landscape of Stonehenge in central Wiltshire.’ The project has largely focused on Durrington Walls; a huge henge enclosure based three miles away from Stonehenge. A roadway from Durrington appears to link Stonehenge with the River Avon. Thus, the project has showed the area around the site to be effectively one large settlement – the largest known Neolithic site in Britain – dating to around 2,500 BC.

In 2007 the area around the standing stone known as the Cuckoo Stone was excavated, revealing Bronze Age cremation burials and pottery urns. The ruins of a Roman temple were also found, showing that the area around Stonehenge had been continually revered as a holy site for over two thousand years. In the same year the Stonehenge Cursus, a mysterious linear structure half a mile long, was discovered.

Experts have deduced that this ditch-like monument was used as a means of sanctifying the surrounding area; a conclusion strengthened by the fact that very few artefacts or remains have ever been found in the curcus. Another startling piece of information is that the curcus dates back to between 3,630 and 3375 BC – predating Stonehenge by up to a thousand years.

Excavation projects such as the Riverside continue to be carried out at and around Stonehenge, and the public’s adoration for the monument as one of Britain’s few true Neolithic treasures remains strong thanks to the ongoing work of its owners, the National Trust. Rightly or wrongly Stonehenge has been classed as one of the seven greatest wonders in Britain, and if its next hundred years are anywhere near as eventful as its last then our children will have learnt a great deal about Britain’s ancient history.