Before you answer that question, let me just point out that Monte Testaccio is actually both, being possibly the oldest Roman rubbish dump to have been excavated and studied in depth. Admittedly an open-air land fill site might not fit in with your idea of a cultural tourist destination and it probably won’t tick the boxes if you’re thinking about glamorous ruins where emperors and senators once set out the course of history. But this pile of old rubbish, as I affectionately like to call it, can tell us a surprising amount about the inner workings of the Roman empire. Where else could you learn that the average Roman consumed about 26 litres of olive oil per year? Or that the Romans ran their imports/exports business with a methodical organisation that surpasses that of many modern governments?

Monte Testaccio – also known as Monte dei Cocci (Testaccio from the latin testae, meaning crockery or broken terracotta pieces – or cocci in modern Italian) – was an active rubbish dump in the first three centuries of the empire. The exact date of its origin hasn’t been established, but it is thought it could have begun its life as early as the first century BC, but certainly by the time of Augustus. It was disused after 260 AD, so it is fair to estimate that it must have been in use for about 250 years at least.

Keeping the Cogs of Rome Well-Oiled

The site is inside the Aurelian wall, which was built between 271 and 275 AD, so Monte Testaccio was probably already disused by the time Aurelian started to build his city defences. It is situated behind what used to be the principal river port of Rome, and some remains of the huge warehouses that served Rome’s imports industry are still near the banks of the Tiber. The port and the huge warehouses are evidence of the high level of organisation and industry needed to run the empire’s hub.

Monte Testaccio is made up entirely of broken terracotta amphorae – large earthenware containers used for transporting produce such as wine, oil or grain. In fact the amphorae dumped at Testaccio were used exclusively for importing olive oil into Rome. It might seem strange that the Romans didn’t think to recycle these heavy containers but according to some experts, it wasn’t possible to reuse them and besides they were so cheap to make (the Romans had huge kilns near to the oil presses in Spain and Africa) that it was more economic to discard the used amphorae.

How to Build a Terracotta Mountain

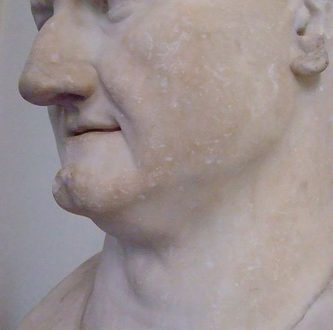

Excavations at Monte Testaccio suggest that 320,000 amphorae were deposited there each year. Each amphora weighed 30kg when empty, and had a capacity of about 65 litres when full. The Spanish amphorae found at Monte Testaccio, identified as Dressel 20 type (after the Italian-Prussian scientist Heinrich Dressel who excavated the site in 1827), are all remarkably uniform, between 70 and 80 cm high and about 60 cm wide.

Some are marked with red or black writing, known as tituli picti, which show a rigorous control and monitoring system. These trade marks show both where the amphora was made and where its contents were from, as well as a control mark to show it had passed quality tests. The Spanish amphorae and the olive oil they contained came almost exclusively from the Roman province of Hispania Baetica, which is modern-day Andalucia. Two-thirds of the amphorae are Spanish. There are also some amphorae at the site from Northern Africa, in particular Tunisia and Libya.

When it came to discarding the containers, the Romans were every bit as methodical as they were in organising the import and distribution of the oil. The amphora would be cut in half horizontally so that the broken pieces of the top half filled the bowl of the bottom half. They were placed side by side and filled until a complete layer was formed – then a second layer would be started on top. The pottery would be covered periodically with a layer of lime to subdue the smell of the rancid oil.

The hill stands 35 metres high, although 15 metres of it are submerged below ground level, bringing the total height of the piles of ceramic pieces to 50 metres. It is likely that it was much higher when it finally fell into disuse in the third century AD – it has since naturally settled and shrunk substantially. It is about 1.5km in circumference, which means there are about 22,000 cubic metres of broken pottery in the hill.

For anyone still in any doubt about how the Romans managed to build Monte dei Cocci, there is an excellent video clip on Youtube that sums it up nicely.

Heading for a Heart Attack?

Monte Testaccio is also testament to the huge amounts of olive oil consumed by Rome’s citizens. Containing hundreds of millions of amphorae, it suggests that over a time period of roughly 250 years, 6.5 billion litres of oil was imported. It is also important to note that this port received imports for the city of Rome only – other Roman towns had their own trade routes.

If we assume that the population of the city of Rome during the first 260 years of the empire was about more or less one million, then consumption of oil per person was 26 litres a year. This sounds like a lot, but it’s not actually so different to average consumption these days. According to statistics from the University of California, modern-day Italians and Spaniards consume on average 14 litres of the green stuff each year, while in Greece the average olive oil quota matches Roman figures of 26 litres a year. But of course in Roman times olive oil wasn’t just used for cooking – it was also burned in domestic and public oil lamps. However, the estimate of 26 litres refers only to imports and doesn’t account for olive oil that was produced domestically.

Monte dei Cocci Through the Ages

The mound of pottery shards has been largely ignored and untouched since Roman times. The first archaeological excavations took place in the late 19th century but until then, people didn’t take much interest in it, preferring to use the hill for other purposes, some of which are extremely strange. During the middle ages it was one of the stages of the Via Crucis, and church processions would march up to the top of the hill, where re-enactments of the crucifixion would take place. There is still a cross on top of the hill marking its past importance as a site of pilgrimage.

Rome’s celebrations and carnival festivities in the period leading up to Lent also focused on Monte Testaccio. While food and drink would be served at hostelries surrounding the hill, some of the traditions ranged from the bizarre to the barbaric. Wooden carts containing pigs and bulls would be pushed to the summit of the hill and would then be left to career down the steep sides, crashing woefully at the bottom. If an animal was unlucky enough to survive the down-hill journey, it would be promptly finished off, dismembered and butchered by the revellers at the foot of the hill.

Another disturbing custom associated with Monte dei Cocci was the annual race through Rome. Second-class citizens – usually Jews and sometimes prostitutes as well – were forced to run a race on foot through the city, ending at Monte Testaccio. The race was nothing more than an opportunity to humiliate and inflict suffering on the poor runners – who sometimes had to run naked and compete against donkeys – and was finally banned by the Pope in 1668.

In the late 17th century cellars were dug out of the bottom of the mound and people found that they were ideal for keeping wine at a cool temperature. The porous consistency of the hill made it a good thermal insulator.

The modern Roman neighbourhood of Testaccio – an area about 1.5km south west of the Roman Forum, and directly west of via Ostiense and the Pyramid of Cestius – is a lively working-class area that has so far just about managed to avoid gentrification (unlike Trastevere, just over the Tiber, which was also a working-class residential area until a few decades ago, but is now more the stamping ground of tourists and Rome’s trendy nocturnal bar-hoppers). Until the 1930s, Testaccio was an undeveloped area of grassland surrounding Monte dei Cocci and it wasn’t until 1936 that residential houses were built there.

Monte dei Cocci now sits in the middle of a busy modern residential area next to the river, and to most passers-by it looks like nothing more than a grassy knoll. Bars and nightclubs have set up business at the base of the hill and many of them have glass walls at the back, to remind drinkers that they are actually sitting inside an ancient Roman rubbish dump.

Photos by Bija Knowles.