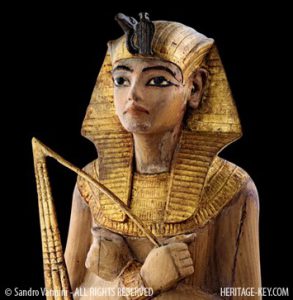

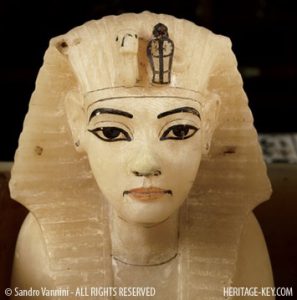

The only such figure found in the Antechamber, it is one of the largest of the servant statuettes. The inscription records the shabti spell from the Book of the Dead, ensuring that the king would do no forced labor in the afterlife.

CREDIT: ©2008 Sandro Vannini

Tut has returned to Toronto. After 30 years the boy king’s treasures are back in the Canadian city, with a new show set to open this Tuesday, at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

It’s the first time the king’s been in town since 1979. In that year Egyptomania was at its height, and Steve Martin was doing his King Tut dance and all.

Before the media preview began today, the organizers tried to re-create a little bit of that 1970’s magic. A pair of dancers from the group ‘For the Funk of it’ performed a tutting dance routine in front of a crowd of journalists and VIPs.

Matthew Teitelbaum, CEO of the gallery, announced that there will be more tutting to come: “We intend to set a world record for tutting.” The museum will try to get as many people to “tut” on the same day as possible.

We also heard that – on the day the exhibit opens – the CN Tower (a 553 metre tower that used to be world’s tallest freestanding structure), Casa Loma and the Hockey Hall of Fame, will be bathed in golden light, all night long, in honour of the pharaoh’s return to Toronto.

A gesture certainly fit for a pharaoh.

Power play

If I were to sum up the exhibition, in one word, it would be this – Power.

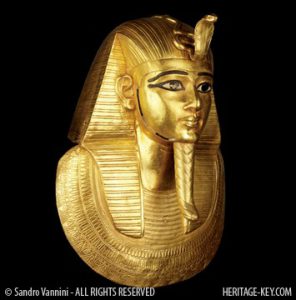

The golden mask lay over the head, chest and part of the shoulders of the mummy of Psusennes, as a layer of protection. The royal headdress with ureaus cobra and the divine false beard he wears attested to his royal and godly status. The use of gold, considered the flesh of the gods, reaffirmed his divinity in the afterlife

CREDIT: ©2008 Sandro Vannini

From the moment you enter, you are confronted – not by the ordinary inhabitants of Ancient Egypt – but by the pharaohs themselves.

The first thing you see, while you’re waiting to get in, is a blue and red sign that reads – “Pharaoh – a ruler almost divine on earth, a god into the afterlife.”

After going through this door, you arrive at a gate that – for some reason – made me think more of Jurassic Park than ancient Egypt. While you’re in front of the gate there is a short video narrated by Harrison Ford explaining the bare basics of what ancient Egypt is and what pharaohs are. After he’s done talking, Ford invites you to enter, the gate opens and you’re in.

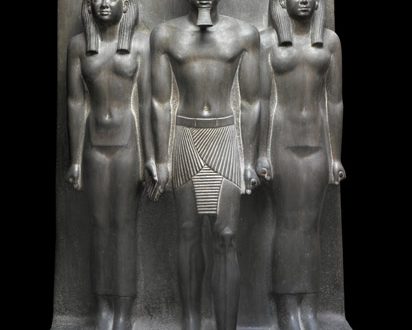

Now – this is where the power comes in. The first room is full of about a dozen statues of ancient pharaohs. This is a very remarkable sight. Egyptian royalty had their statues carved in a way that is ultra-formal. No smiles, all rigid poses and a sense that the pharaoh is glaring at you.

In this single room stands a calcite statue of Menkaure (found in Giza) and Khafre (from Mit Rahina). Also seen is a statue of Thutmose III, offering liquid to the god Amun. There is also a red granite statue of Hatshepsut, who is kneeling and offering a jar of liquid to the gods.

Gilded wood, rock crystal, and coloured glass

Height 13 cm

Photo by Matthew Prefontaine

A statue of Ramses II, from Tanis, has his Ureaus and sceptre, and a clay-stucco statue of Amenhotep III has a blue crown.

You are surrounded by a dozen of these pharaohs in total, all with the same formal, rigid, rendition. They are separated by as much as 1,000 years in time – but they are all together in this one room – arranged in such a way that they all face the viewer at once.

I’m not aware of an archaeological site in Egypt where the statues of so many pharaohs – from such a broad stretch of time – are clustered together in a single room. It’s powerful stuff – and it’s a feeling that cannot be truly conveyed through any means other than by being there.

The Pharaohs and Their Treasures

The next three rooms flesh this feeling out, giving you insight into the life of a pharaoh – their officials, their religion, and of course, their treasures.

Numerous colossal sandstone images of Amenhotep IV enhanced the colonnade of the kings temple to the Aten at East Karnak. The double crown, atop the nemes-headdress, alludes to the living king as representative of the sun god.

CREDIT: ©2008 Sandro Vannini

It becomes clear quickly that this is not an exhibition about the ordinary workers, rather, this is about the men (and women) at the top.

One of my personal favourites is a sketch of an Amarna princess, with a distorted head and body, that is typical of this period, eating duck. It appears to be a trial piece, done by an ancient artist trying to get just the right look.

Another fav of mine is a well made limestone sarcophagus holding Prince Thutmose’s cat (18th dynasty) – a picture of the cat is on both sides of the box. It’s a touching display of affection.

Another pharaonic moment is captured in a stela that shows an official called ‘Any’ riding in a chariot (the charioteer has the elongated skull of the Amarna period). He has just received the “gold of honour,” an award that was given to him by Akhenaten himself. Any certainly seems quite proud.

A giant statue of Akhenaten, pictured here, which appears to date to the early days of his reign, is the biggest object in any of these rooms. His elongated face has yet to be fully twisted into the weird egg-shaped presentation that will be seen later in this period.

Another key treat is the golden funerary mask of Psusennes I – it dates to the Third Intermediate Period. It’s a beautiful object, shown in the section above, that was created for a rather obscure king. He lived at a time when Egypt was not fully unified.

It’s interesting to note that – if King Tut’s tomb had been completely robbed – he also would not have become a household name.

Gold

Width 33 cm

Photo by Matthew Prefontaine

By now you’ve read the names of a lot of different pharaohs – from many different time-periods. Khafre dates to the Old Kingdom, Akhenaten is from the Amarna Period, and there are kings from the Middle Kingdom that are featured in this exhibition as well.

This is the one potential drawback of the exhibit. If you don’t have a good grasp of the time periods of ancient Egypt (Old Kingdom, first intermediate, Middle Kingdom, second intermediate, etc…) You might find yourself a little lost in time.

The best thing I would recommend would be to read a good general history book on Egypt, such as Ian Shaw’s book, History of Ancient Egypt.

Alternatively, if you don’t have the time, the museum offers an audio tour narrated by Harrison Ford that will help you out. It’s on a handheld device that you pick up as you enter the exhibit.

King Tut’s Treasures

The second phase of the exhibit features the treasures from King Tut’s tomb.

It’s layed out in the same way that Tut’s tomb is organized – the antechamber, the annex, the treasury and the burial chamber. Each room holds the treasures that were found in it.

A large container with four hollowed out sections held the internal organs of the king. Each of its compartments had a lid in the form of Tutankhamuns head. The royal name on both the chest and its outer shrine appears original, suggesting that Tutankhamun did not usurp the container from a predecessor.

CREDIT: ©2008 Sandro Vannini

The first thing you see are wall-sized photographs of Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon, beside a black and white photo of workers digging out Tut’s tomb.

“Yes, wonderful things,” Carter says in a video that is playing.

When you go into the antechamber you actually have to duck if you’re more than 6’2.

“As my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist. Strange animals, statues of gold…” says a quote by Howard Carter that is on the wall, from his notebooks, which are currently in the Griffiths Institute.

The exhibition does not disappoint. King Tut’s bed, a meter-long wood construction, is the first thing that I notice.

The head of a leopard, made with gold and wood, is also seen. It was found in context with robes. The priests attached it to them when they performed “the opening of the mouth” ceremony.

A beautiful shabti, with a face that looks so much like Tut, is on display. Sandro Vannini captured it in a terrific photograph that leads off this piece. Shabtis did the work of the deceased in the afterlife – there were 413 found in King Tut’s tomb. With that many, he wouldn’t have to lift a finger after he was gone!

Necklaces of beads, a ring with scarab bezel, there are many, many more treasures on display.

These golden sandals have engraved decoration that replicates woven reeds. Created specifically for the afterlife, they still covered the feet of Tutankhamun when Howard Carter unwrapped the mummy.

CREDIT: ©2008 Sandro Vannini

The Annex is the next stop. “Everything was in confusion and there was not a vacant inch of floor space,” – another quote by Howard Carter, on the walls of the exhibit.

A headrest made of glass and gold, faience shabtis, a one meter tall chair with an image of Horus engraved on the back. A model of a scribal palette – could it be used for writing in the afterlife? A pendent with a royal cartouce.

I had to take a breath from time to time, as I looked through Tut’s treasures. It is the first time that I have seen them in person. It’s a much different experience than seeing them in a book or online.

As you go on and on you expect to see something even more grander – next the treasury.

A model of a boat is the first thing that I saw in this room, made of wood with some of its paint still remaining, it has one oar and is about a meter long. There are more shabtis, golden, grey, blue and red – one of each color!

A brown, plain looking wooden box is there. It seems out of place, looking unremarkable compared to Tut’s other treasures. But then I look at the inscription – it held two fetuses that may have been King Tut’s daughters. There’s a sad story to this item.

There is a canopic stopper – in the image of the pharaoh – and it holds four compartments. It would have held the internal organs of the king. Again, Sandro Vannini has a terrific photograph.

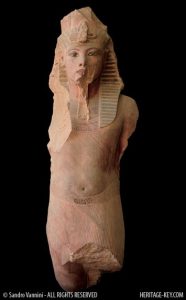

This colossal statue of Tutankhamun was found at the remains of the funerary temple of Ay and Horemheb. The belt is inscribed with the name Horemheb, written over the earlier names of Ay and Tutankhamun.

CREDIT: ©2008 Sandro Vannini

Next, the burial chamber – “an astonishing sight, a solid wall of gold” is the quote from Carter.

There is a fan, one of eight found in the tomb, with an ebony pole. There are Djed, Wadi and Horus amulets, 3 of the 25 that were found on Tut himself.

A winged uraeus amulet, vulture amulet and double uraeus amulet. A cobra collar, pictured in this article.

The most prominent artefact is a golden pair of sandals, decorated and engraved. They were found on Tut’s feet, as a photograph behind the artefact shows.

Now, this exhibit isn’t going to end with Tut’s sarcophagus – that particular item is no longer let outside of Egypt. But this exhibit has its own unique ending.

As you step into the final room you see a 10 foot tall statue of King Tut, towering in front of you. It may have originally been in his mortuary temple. After Tut’s death, King Ay appropriated it and carved his name on the belt. Horemheb, in turn, took it over for himself and re-inscribed the belt.

Although it looks plain today, there is some residual paint on it, pointing to a time when it would have been alive with colours.

And that’s how the exhibit ends – the way it begins really. The pharaoh staring down at you – with all his power and religious might.

Tutankhamun: The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs was previously in Indianapolis, and Keith Payne picked out his favourite artefacts from that leg of the exhibition – many of which you can see in King Tut Virtual right now. He also got the chance to interview Dr Zahi Hawass.

The exhibition will be at the Art Gallery of Ontario from Tuesday 24 November 2009 to Wednesday 31 March 2010. We’ll be reporting from the Toronto exhibition, so check out Heritage Key for more information on the most popular Pharoah in town.