Can a modern couch potato be trained to fight like a Roman gladiator? That’s a question that a group of students and experts in Germany are trying to answer with an experimental archaeology project, using expertise from ancient history together with sports science.

Can a modern couch potato be trained to fight like a Roman gladiator? That’s a question that a group of students and experts in Germany are trying to answer with an experimental archaeology project, using expertise from ancient history together with sports science.

Twenty students are being put through their paces to find out how gladiators in ancient Rome might have actually trained for their fights in the arena.

The cross-disciplinary project aims to get a different perspective on a fascinating area of history that is in the limelight following the success of films such as Gladiator and the TV series Spartacus: Blood and Sand.

The project is led by Josef Löffl, a research fellow in ancient history at the University of Regensburg in Germany, who is collaborating with his colleagues from the sports sciences faculty. Together they have devised a training programme that they believe mirrors the conditions found in ancient gladiatorial schools.

Some of the conditions the would-be gladiators will face include:

- A strict diet that will include large quantities of beans, olive oil and whole-grains, with only a small amount of meat. Alcohol and sugar are banned, as are tomatoes.

- Learning to fight wearing authentic Roman costumes, helmets and weapons, some of which were very heavy and cumbersome.

- Fighting bare-foot on sand, which makes quick movements difficult.

- Their weapons, which include wooden swords, will be put to the test against wooden poles.

- An intensive one-month summer school in August will see the 20 trainees confined to their gladiatorial camp.

- Olive oil and a metal scraper will be used to remove sand and dirt from the trainees’ bodies, although Roman-style baths will also be available.

The inspiration for the project came from work done by the famous German historian Marcus Junkelmann, who created replicas of gladiatorial equipment from the first century AD based on findings at Pompeii.

The inspiration for the project came from work done by the famous German historian Marcus Junkelmann, who created replicas of gladiatorial equipment from the first century AD based on findings at Pompeii.

The objects excavated at Pompeii, as well as mosaics, paintings and graffiti, give important information about the helmets, armour and clothes that the different types of gladiators might have worn in 79 AD.

Löffl said: “We really don’t have much information about how gladiators trained. I thought it would be nice to start a new experiment with colleagues from the department of sports sciences at the University of Regensburg, based on the equipment devised by Marcus Junkelmann. We wanted to know how you train people to fight in a gladiatorial outfit.”

You Are What You Eat

The equipment, diet and type of training are based on several historical and archaeological sources. For example the swords used (albeit just wooden replicas) are copies of the Roman swords that were found at Dangstetten, the site of a Roman military camp in southern Germany near the town of Küssaberg. Other equipment – such as the helmets are based on helmets found at Pompeii, while textiles used are based on archaeological remains at Pompeii.

As for the diets of the gladiators, a lot of information about this comes from a site discovered in 2007, when the tombs of gladiators were found at the site of a gladiatorial school outside the ancient city of Ephesus in Turkey (see this BBC report about it).

As for the diets of the gladiators, a lot of information about this comes from a site discovered in 2007, when the tombs of gladiators were found at the site of a gladiatorial school outside the ancient city of Ephesus in Turkey (see this BBC report about it).

Tests on the gladiator skeletons found there have given scientists a lot of information about the style of combat, diet, weapons and lives of gladiators.

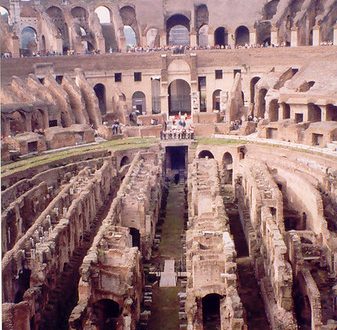

Although the famous gladiator schools are the Ludus Magnus by the Colosseum in Rome and the school at Capua (from which Spartacus escaped), it is thought there were small ludi all over the empire, and they were often associated with military camps, which would often have a small wooden arena nearby.

Other sources such as historical texts have also been used for the project. For example, the writer and medic Galen, one of the founders of ancient medicine under Marcus Aurelius, was also a physician to the gladiators at Pergamum in 157 AD. He wrote that a gladiator had to give his body completely to training and were not to drink alcohol or have sugar.

The Gentleman’s Sport?

Contrary to the image of gladiators in Hollywood films, not all gladiatorial combats in the ancient world would have ended in bloody death. According to Löffl, skill, rules and control would have dominated the fights. One example that Löffl highlights is the fight on the opening night of the Colosseum in 80 AD, which was between two famous gladiators – Priscus and Verus – as described in the Roman poet Martial’s De Spectaculis. The two both fought so well and were such an equal match for each other, that in the end the emperor Domitian recognised them both as the winner.

The gladiators’ skeletons at Ephesus also show that most gladiators had healed wounds on their bodies, suggesting that they had fought many times without dying.

The gladiators’ skeletons at Ephesus also show that most gladiators had healed wounds on their bodies, suggesting that they had fought many times without dying.

Löffl said: “The mortal wounds are often quite clean and there is often only one mortal would – suggesting that, rather than being a gory bloodbath in which gladiators were shredded and mutilated, there was far more control and precision.

The loser of a battle may have been killed at the end – but with one thrust of the sword downwards through the throat and chest.”

Barefoot and Heavily Armoured

The 20 students undertaking the gladiator training are being taught to fight barefoot and on sand. According to Löffl, this was one of the important ways that the real gladiators controlled their combat. It was more difficult to move and run away on sand, so the men were forced to stay and engage in the fight. They were also weighed down by their heavy helmets and equipment. According to Löffl, the gladiators’ helmets found at Pompeii were two or three times heavier than a normal legionary helmet. These two factors imposed some control over the fight.

Gladiators were highly trained sportsmen – they would undergo four to five years of training before hitting the arena. It wouldn’t have been in their owners’ interests to have a top sportsman killed off immediately and, according to Löffl, the skeletons at Ephesus show that they had very good medical care.

However, some gladiators were put in the arena just to be killed and, according to Löffl, some were forced to fight with blinded eyes, without armour or were forced to re-enact deadly scenarios, such as Icarus’s flight from Greek mythology (the poor ‘gladiator’ would be forced to jump from a height and, like Icarus, would crash to his death). Löffl is clear that these unfortunate men were nothing to do with the highly-trained professional gladiators.

It’s Going to be a Long August

The 20 students at Regensburg, together with four trainers from the department of sports science, started their gladiatorial training in March in a modern sports hall but will soon progress to fighting on sand. During August they will spend a month living a more authentic gladiator’s life.

Löffl said: “It’s a very slow beginning, they have to learn how to fall first of all. They are now starting to fight using wooden weapons and are practising the movements. The final stage of the project will be in August, when the students will fight in a real Roman amphitheatre in Carnuntum, near Vienna. They will live for a month in the same conditions that were found in a gladiatorial school. They will eat, train and fight like the Roman gladiators.”

Löffl said: “It’s a very slow beginning, they have to learn how to fall first of all. They are now starting to fight using wooden weapons and are practising the movements. The final stage of the project will be in August, when the students will fight in a real Roman amphitheatre in Carnuntum, near Vienna. They will live for a month in the same conditions that were found in a gladiatorial school. They will eat, train and fight like the Roman gladiators.”

The students will be training on sand and will practice their fighting moves against wooden poles.

Löffl added: “Certain types of gladiators would only fight against certain other types, so we will be training according to those rules too (which we know from Roman sources such as mosaics).”

Big gladiatorial schools had baths – but there was a big different in how gladiators would have gone about their daily hygiene. After a fight they would have been covered in sand, so instead of going straight into a bath, they would use olive oil to cover their bodies, then remove the mix of oil, dirt and sand with a metal scraper.

When the gladiators have come to the end of their training, Löffl is hoping to write a book about the experiment, including personal accounts of the students who participated, details the training programme as well archaeological material used in the project

All images courtesy of Natalie Glas.