Recent archaeological work at the site of Tell Tayinat in southeast Turkey, near the Syrian border, indicates that the ancient city was the centre of a Dark Age kingdom, ruled by people from the Aegean area. In an in-depth interview Professor Timothy Harrison, of the University of Toronto, told Heritage Key about this startling theory and the evidence that supports it.

Around 1200 BC life changed suddenly throughout the Mediterranean world. The Mycenaean civilization in Greece and Crete, the Egyptian New Kingdom and the Hittite Empire, all collapsed at roughly the same time.

It’s not until 900 BC that archaeologists consider the Dark Age to be over – at least in the Syrian area. In the years after it ends, the Assyrian empire is re-born, Greek civilization flourishes and Egypt (eventually) re-unifies.

Political turmoil caused by the migration of a group known as the “Sea People” is a reason many historians give for the collapse. This poorly understood migratory wave of people, quite possibly from the Aegean area, is attested to in historical documents.

There are also records of famine and, as such, it is possible that environment change could have been a cause as well.

Few written records exist from this time-period (hence the term “dark age” to describe it) and it appears as if there were no large, unified, empires.

A tale of Two Ancient Cities

Tayinat had been abandoned for 800 years when the Dark Age hit. Only meters away however, a city named Alalakh flourished. It had been a key settlement for several local power groups and was controlled by the Hittites when the Dark Age hit the Middle East.

When the collapse came, Professor Harrison explained, Alalakh was either destroyed or abandoned. However, at almost the same time that Alalakh became uninhabited, Tayinat was re-settled.

Why one city (Alalakh) would collapse, and another (Tayinat) would re-appear – only meters apart from each other – is a mystery.

One idea is that migrants to the area, arriving just as the Dark Ages start, saw that Alalakh was occupied and Tayinat was free. If you follow this line of thought, there were few areas in the vicinity that could support a large settlement. Tayinat, although it was in ruins, happened to be elevated, giving it protection from flooding and military attacks.

It then follows that Alalakh was destroyed or became abandoned and Tayinat – somehow – held out.

Another idea – and one that gained traction after work done last summer – Is that there was a shift in the Orontes River that made Tayinat a more desirable place than Alalakh.

“Maybe part of what happened is that the river shifted its course a little bit,” said Professor Harrison.

People from the Aegean

When the archaeologists dug down to the deepest occupation layers at Tayinat they were startled by what they found. They discovered a large number of artefacts that looked as if they were made by people from the Aegean.

To understand why this is a big change you have to look at how things were before the Dark Ages hit. At Alalakh, before the Dark Ages, there were Mycenaean pottery and luxury goods, but it was obvious that they had been imported through trade.

At Tayinat it was different, the goods were being made locally – they were not imported.

“Now it’s a local product, rather than imported Mycenaean pottery,” said Professor Harrison. “For example what were finding is a locally produced variant of the late bronze age Mycenaean wares.”

Aegean influences were also seen in textiles and figurines. There is also some faunal evidence emerging that the people may have consumed a diet that was reminiscent of the Aegean.

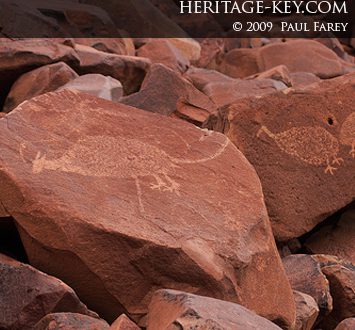

But some of the most intriguing evidence is in the form of writing. A few signs of what appears to be Cypro-Minoan script have been found. Cypro-Minoan is an un-deciphered language found mainly in Cyprus – so what was it doing there at Tayinat?

It’s difficult to say for sure how large the settlement was during the Dark Age, although Harrison describes it as a “significant urban centre in ancient times”. He speculates that it could be up to 12 hectares large, possibly having around 2,500 people. In the centuries after the Dark Age (9th/8th centuries) the settlement had grown to nearly 40 hectares, with a population that may have been around 10,000 people.

Architecturally, the earliest buildings found date to the 12th century BC. They are described as being “modest,” and “industrial.” The team is still investigating what each of them was used for.

The most intriguing find dates to the 11th/10th century BC. It’s a structure named “building 14”, which may be as big as 100 meters by 50 meters in size. It was partially excavated in the 1930s and archaeologists are now returning to it. It has walls three meters thick and was “clearly monumental in scale.” Its use is unknown.

There have been several reports over the past few months that the team had found a Dark Age temple dating to the 10th century. However, those reports are not entirely accurate.

Professor Harrison clarified the matter last month, telling me that so far the team has only excavated the temple as deep as the 9th/8th centuries, a time-frame after the Dark Ages. It’s possible that the temple does have foundations during the Dark Age period, but the team has not dug down to those levels yet and cannot say for sure.

A Dark Age Kingdom?

The idea that these Aegean people who came to Tayinat formed a Dark Age Kingdom is controversial and Harrison concedes that, for now, it’s a “radically new proposal” that is more hypothesis than fact.

Aside from the archaeology, another part of this argument, that a kingdom existed, is a number of Luwian inscriptions found at Tayinat and other sites in the Near East. They give fleeting looks at a kingdom named Palastin or Walastin, that Professor Harrison believes may have had its capital at Tayinat.

Historian Dr. John Hawkins has done work on these inscriptions and helped to develop this hypothesis.

One Dark Age inscription, found at Aleppo, refers to a ruler named Taitas, describing him as “Hero and King of the land of Palastin”.

Two other inscriptions have turned up (out of context) that refer to a Queen Kupapiyas as “Wife of Taitas”, who is in turn referred to as the king of “Walastin.”

Another inscription, this time found at Tayinat, refer to a Halparuntiyas who “Ruled the land of Walastin”.

The most famous possible reference is at Medinet Habu in the Luxor area of Egypt. A stele found here describes pharaoh Ramses III’s conflict with the sea peoples. It’s been proposed that the name “Peleset,” in the inscription means Palastin/Walastin.

The inscription reads in part (from a translation by James Henry Breasted):

They came with fire, prepared before them, forward to Egypt. Their main support was Peleset, Thekel, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh. These lands were united and they laid their hands upon the land as far as the circle of the Earth.

Assyrian Conquest and Tablet Discovery

In 738 BC Tiglath-pileser III, ruler of a resurgent Assyrian empire, made a visit to Tayinat. He destroyed the city, captured its ruler Tutammu and rebuilt it as a provincial capital.

Tiglath-pileser goes on to brag about it in an inscription…

(From a translation by Hayim Tadmor)

In my fury of … Tutammu, together with his nobles … I captured Kinalia, his royal city. His people, together with their possessions … mules I reckoned like sheep [distributing them] among my army … I set up my throne right inside Tutammu’s palace

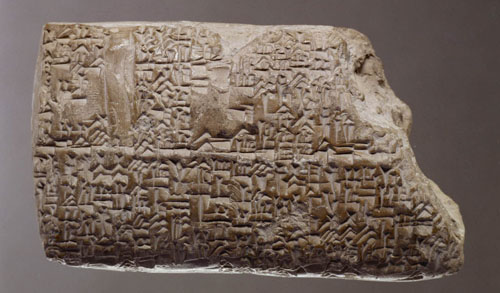

Last summer, at a temple that dates to this era, the team found a cache of tablets that date to the Assyrian occupation of Tayinat. Professor Harrison told me that the largest one is 45cm by 35cm in size, and took nearly eight hours to excavate.

It’s going to be sometime before the team knows what they say. Harrison explained that the find was made near the end of their last field season. The tablets have to be conserved and cleaned before serious translation work can begin.

Some of the documents are certainly administrative.

One of them “is essentially like a spreadsheet, has a variety of commodities, mostly agricultural, like wheat, emmer, things like that,” said Professor Harrison. “It’s basically some kind of listing of information.” The document also has a listing of numbers that are arranged according to months of the year.

“Since these tablets were found in the inner sanctum of the temple, it’s tempting to see them as perhaps part of a temple archive,” he said.

“Maybe this one tablet might have something to do with recording or provisioning of the temple or offerings being made or something like that.” He added that it’s too early to say for sure.

Some of the documents might well be literary or historical, Harrison said. The 45 cm by 35 cm tablet isn’t likely to be a commodity list. “The format of the document indicates that it’s clearly either a literary or historical document it may well prove to be something like a royal inscription.”

The Fall of Tayinat

How Tayinat met its end is a mystery. The site was abandoned or destroyed by an unknown group, perhaps as early as the 7th century.

“We don’t when, we don’t know why and we don’t know by whom,” said Professor Harrison. “(It’s) sort of like another dark age.”

This abandonment would last until Hellenistic times when the area had a massive resurgence. Only a few kilometres away from Tayinat, the city of Antioch was founded in the 4th century BC.

Founded by one of Alexander the Great’s generals, it became an important centre during the time of the Seleucid Empire. When the Romans took over the city, it continued to grow, becoming a “second Rome,” with a population that some estimate to be around 400,000 people.