Angelina Jolie will play Cleopatra, the last queen of Egypt, in a film adapted from Stacy Schiff’s upcoming book ‘Cleopatra: A Life’. It’s hardly likely to subdue those arguing Cleopatra was little more than ‘Egypt’s sex kitten’ (opposed by myself, Nele and Rosemary Joyce in her blog and book ‘Ancient Bodies’, I must say), but it’s exciting news nonetheless. The book won’t be published until autumn 2010, but producer Scott Rudin has already purchased film rights, saying the movie ‘is being developed for and with Jolie’. Author Schiff has even hinted at Brad Pitt playing Roman general Mark Antony, reminding…

-

-

In an interview for Toronto-based ‘The Agenda’, journalist Steve Paikin questioned Dimitrios Pandermalis, president of the New Acropolis Museum in Athens, on why Greece believes the famous Elgin Marbles should be returned to their homeland. And if the British Museum were to return the marbles would it not set a precedent for a myriad other claims for reparation, from all over the world?Pandermalis sees the return of the Parthenon Marbles not as a ‘repatriation’ of artefacts, but rather as re-unification, reinstating the ancient monument’s integrity. Pandermalis is right to say that the Parthenon sculptures and friezes do not belong to…

-

A 5,500-year-old leather shoe has been found in a cave in Armenia. The shoe 1,000 years older than Giza’s Great Pyramid and 400 years older than Stonehenge is perfectly preserved and was found complete with shoelaces. It is believed to be the oldest example of enclosed leather footwear, out-dating the shoes worn by Otzi the Iceman by a few hundred years. The shoe is sole-less, made out of a single piece of cow hide and was shaped to the wearer’s right foot. It contained grass, which might have served to either keep the foot warm or to maintain the shape…

-

The exhibition ‘Cleopatra: The Search for the Last Queen of Egypt’ premired this weekend at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. Blogs and major newspapers have been in awe about the exhibition, featuring the amazingphotographs from the underwater excavations by Franck Goddioand articles about Cleopatra’s glamour and quite disastrous – love life. There’s nothing but praise for the ‘beautiful queen’ and mass coverage on the two quests for her tomb, where she rests with lover Mark Antony. But a true must-read before visiting the exhibition is Rosemary Joyce’s critical blog entry on how we perceive the last Queen of Egypt. She…

-

When you see Dr Bob Brier lecturing about mummies, there is no doubt he’s passionate about them. The same goes for Dr Salima Ikram and all kinds of animal mummies (watch the video). But actual love between an archaeologist and a mummy? That’s something reserved solely for B-movies, until now: Musician Josh Ritter chronicles the love between an archaeologist and a mummy she discovers in Egypt, on new album ‘So Runs the World Away’. Aptly named ‘the Curse’, the song is accompanied by an enchanting puppet music video. When they are on their way from Egypt to New York by…

-

A Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) pilot survey at the New Forest National Park has revealed previously unknown features to archaeologists. The data, from a a 34 square kilometres section of the New Forest between Burley and Godshill, has allowed researchers to identify a wide range of features, from Iron Age field systems and Bronze Age burial mounds (known as barrows) to anti-glider obstacles, a practice bombing range and a searchlight position from World War II. Normally archaeologists rely on lengthy and labour-intensive field surveys to uncover such features, but airborne Lidar helps speed up the process. Tom Dommett, carrying…

-

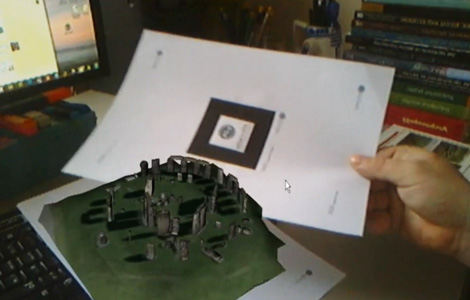

Augmented Reality (AR) seemed a pipe dream not long ago, but today you’ll find AR Japanese girlfriends (no kidding), pets – or ‘Petz’ – for your kids, tattoos, travel applications (read:iPhone or Android-based systems). In fact fighter pilots have been using it for ages (head-up displays for navigational purposes, not Japanese girlfriends, of course). But I must say this is the first ‘AR Stonehenge’ I’ve come across. Take a look at the video below – I’m sure you’ll agree it’s pretty impressive. Augmented Reality – a reality in which virtual, computer-generated images overlay the physical environment, and thus enhance it…

-

It’s the kind of myth that has always had the power to fascinate people: a beautiful, wealthy and sophisticated ancient city is swallowed up by forces beyond man’s control, destroyed by the sea and earthquakes. There are examples around the world of these mythical submerged cities. We not only have Atlantis somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, but in Taiwan there’s the legend of the submerged Mudalu, in Wales there is a drowned city called Cantre’r Gwaelod and a similar story tells the tale of Ys, a drowned city off the coast of Brittany in France. They are all myths that…

-

The Egyptians cut their multi-ton bricks so precise that, often, no mortar was needed for the construction of their monumental builds. The Romans mixed volcanic ashes in their ancient mortar, ensuring the Trajan Forum lasts for almost 20 centuries now. The ancient Chinese builders, however, opted for a more culinary solution: sticky rice mortar. Scientists have discovered the the secret behind an ancient Chinese super-strong mortar made from sticky rice, concluding it still remains the best material for restoring ancient buildings today. The mortar a paste used to bind and fill gaps between bricks, stone blocks and other construction materials…

-

Nowadays nobody could imagine Italian cuisine without tomatoes, aubergine, potatoes, maize or pasta as we know it today. The ancient Romans had none of those ingredients available to them. Then what did they eat (besides flamingo)? I visited the ‘Feasting’ event at the British Museum to find out. In the early years of the ancient kingdom of Rome, dining habits were quite alike for all Romans, rich or poor: breakfast (or ientaculum) in the morning, a small lunch at noon and the main meal of the day, the cena, in the evening. Barely any food was roasted; instead the food…