Tutankhamun has always captured popular imagination, and been a major draw for museums. The British Museum’s 1972 exhibition of artefacts from his tomb smashed all expectations in the box office, drawing over 1.6 million visitors over its nine month duration. The pharaoh nicknamed ‘King Tut‘ has been the source of more speculation, satire and popular culture references than any other male king of Egypt. Last week pathologists announced the results from their studies into the genetic relationship of eleven mummies from the Egyptian New Kingdom (mid 16th to early 11th centuries BC), including those of the legendary pharaoh Tutankhamun.

Tutankhamun has always captured popular imagination, and been a major draw for museums. The British Museum’s 1972 exhibition of artefacts from his tomb smashed all expectations in the box office, drawing over 1.6 million visitors over its nine month duration. The pharaoh nicknamed ‘King Tut‘ has been the source of more speculation, satire and popular culture references than any other male king of Egypt. Last week pathologists announced the results from their studies into the genetic relationship of eleven mummies from the Egyptian New Kingdom (mid 16th to early 11th centuries BC), including those of the legendary pharaoh Tutankhamun.

The genetic testing revealed the identities of three generations before him, his great grandparents (Yuya and Thuya, the two best preserved of the mummies in terms of facial recognition), his grandparents (Amenhotep III and Tiye) and his unidentified father (known for now as KV55) and mother (KV35YL). The study – airing as ‘King Tut Unwrapped’ – did reveal that Tutankhamun’s parents were part of one of the notorious incestuous marriages of Egyptian royalty. There is speculation that this unidentified mother (and Aunt) was Kiya. Kiya was the favourite of one of the most notorious of pharaohs and strongest candidate to be the mummy found in KV55: Akhenaten.

We have come tantalisingly close, through this study, to answering one of the enduring mysteries of Egyptology. Who is the mummy known as ‘KV55’? Before this investigation, KV55 was considered too young to have been Akhenaten. However, this study found that the mummy could have died at around 60 years old. Found amongst the other tombs of the Amarna period, could it be Akhenaten – the king whose successors tried to wipe him from history? Akhenaten forced through religious reform, ending the worship of all other Egyptian gods apart from one: Aten. His status as the ‘heretic’ king may have lead to his reburial in Thebes, after his original tomb had been desecrated.

The British Museum has a fragment of a statue depicting Akhenaten. Even though only the lips and nose are intact, archaeologists can still be confident that the statue depicts Akhenaten due to the unusual artistic style which was trademark of his era. With full lips and long face, it was thought for many years that he suffered from a genetic disorder which had led to a deformed physical appearance; this study has finally been able to put that theory to bed.

Perhaps one day the whole family – KV55, Tutankhamun and all – will make the trip to be seen together at the British Museum and the other leading museums of the world. In the meantime, we can still see artefacts relating to some of these ancient rulers within Britain. The British Museum holds in their collection a stela with the image of Akhenaten portrayed in the Amarna style. He sits in a relaxed pose, seated, with a protruding chin and rotund little belly. Curiously, he also has what seem to be developed breasts, leading to speculation he suffered from Gynecomastia – male breast growth which is also now disproven and currently accepted as another stylistic fad. Above him in this picture, the Sun casts down its rays, the gift of Aten. Is this figure themummy KV55? The evidence is mounting.

Perhaps one day the whole family – KV55, Tutankhamun and all – will make the trip to be seen together at the British Museum and the other leading museums of the world. In the meantime, we can still see artefacts relating to some of these ancient rulers within Britain. The British Museum holds in their collection a stela with the image of Akhenaten portrayed in the Amarna style. He sits in a relaxed pose, seated, with a protruding chin and rotund little belly. Curiously, he also has what seem to be developed breasts, leading to speculation he suffered from Gynecomastia – male breast growth which is also now disproven and currently accepted as another stylistic fad. Above him in this picture, the Sun casts down its rays, the gift of Aten. Is this figure themummy KV55? The evidence is mounting.

Unlike Akhenaten, Amenhotep III is well represented in the archaeological record and within British museums. He was cast in a relief dating to after his death in the style preferred in the time of Akhenaten. He sits alongside Queen Tiye, mother of the elusive KV55, in a familial pose characteristic of the Amarna period, where Kings celebrated their marriages and family status.

More impressive perhaps are the two colossal works in the museum’s collection. One is an almost three metre high head, without the full lips that the Amarna kings preferred. Why the inconsistency? It was common practise for pharaohs to usurp monuments to other kings. Rameses II rededicated some of Amenhotep’s sculptures to himself, and in doing so the peculiar physical features were corrected, the lips ‘trimmed’ and the paunch in the gut reduced to conform to what the great propagandist Pharaoh Rameses II believed was the ideal – or perhaps better suited his vanity.

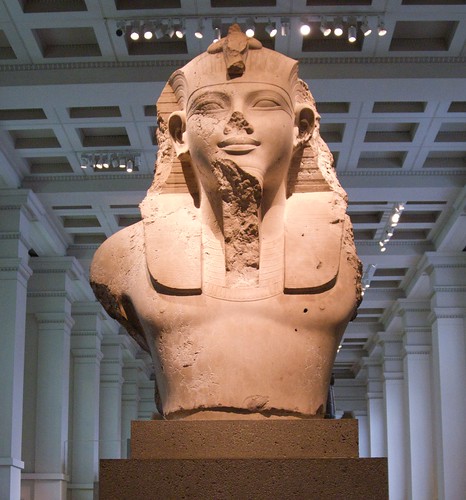

The colossal head wears the crown of both Egyptian kingdoms. Cut from smooth granite it is in superb condition apart from the loss of the goatee beard (and the rest of the body, of course). A different head of Amenhotep III was reunited, in replica, with the accompanying body on the original site in Egypt, just under a year ago. The ruler was one of the pioneers of colossal sculpture. One of the most impressive artefacts from the Amarna period and the ancestors of Tutankhamun within the UK is a limestone bust, around a metre and a half tall. The torso, head, face and headdress featuring a coiled cobra – are very well preserved, and it wears a Mona Lisa type smile of contentment.

The colossal head wears the crown of both Egyptian kingdoms. Cut from smooth granite it is in superb condition apart from the loss of the goatee beard (and the rest of the body, of course). A different head of Amenhotep III was reunited, in replica, with the accompanying body on the original site in Egypt, just under a year ago. The ruler was one of the pioneers of colossal sculpture. One of the most impressive artefacts from the Amarna period and the ancestors of Tutankhamun within the UK is a limestone bust, around a metre and a half tall. The torso, head, face and headdress featuring a coiled cobra – are very well preserved, and it wears a Mona Lisa type smile of contentment.

Finally, we have a seated black statue of Amenhotep III, 235 centimetres tall, albeit made of fragments and recreated parts. Hundreds of these statues would have been commissioned to commemorate his death, and they would have once watched over the place of his burial complex.

Now that genetics has unravelled the connections between the mummies, the intertwining of these influential lives has been revealed. It is fascinating that after so many eras and generations the mists of time are clearing. The eighteenth dynasty, which stuttered after the death of the ‘Golden King’ Tutankhamun, is now of more interest than ever before. The more complete picture we have before us now would be superbly complimented by an in-depth exhibition to present these people through their monuments together, as they were tied together to each other by blood, a great family remembered millennia after their deaths.

More information on the most recent ‘King Tut family’ research in Discovery Channel’s ‘King Tut Unwrapped’ documentary, which will air on March 3 & 4 in the UK, here’s a photo preview. If we’ve overlooked any of King Tut relatives who have artefacts currently in London or Oxford, !Surprised by so many Amenhotep IIIheads? Yet another one has recently surfaced in Luxor. No King Tut treasures on display in London (as far as we know, feel free to correct) but of course, you can have an up-close look for yourself in King Tut Virtual.