Penn Museums world-renowned Mesopotamian Collection from Ur is the centrepiece of a new long-term exhibition exploring Iraqs Ancient Cultural Heritage that opens October 25th.The exhibition will contain field notes of previous expeditions to the region, photographs, archival documents as well as more than 220 extraordinary ancient artefacts unearthed at the excavation. Famous artefacts such as the Ram-Caught-in-the-Thicket, the Great Lyre with a gold and lapis lazuli bull’s head, and Queen Puabi’s jewelry, as well as her headdress and other treasures, will be on display at ‘Iraq’s Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur’s Royal Cemetery‘.

Penn Museums world-renowned Mesopotamian Collection from Ur is the centrepiece of a new long-term exhibition exploring Iraqs Ancient Cultural Heritage that opens October 25th.The exhibition will contain field notes of previous expeditions to the region, photographs, archival documents as well as more than 220 extraordinary ancient artefacts unearthed at the excavation. Famous artefacts such as the Ram-Caught-in-the-Thicket, the Great Lyre with a gold and lapis lazuli bull’s head, and Queen Puabi’s jewelry, as well as her headdress and other treasures, will be on display at ‘Iraq’s Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur’s Royal Cemetery‘.

In 1922 – the same year that Howard Carter made headlines with the discovery of Tutankhamun‘s tomb in the Valley of the Kings – the Penn Museum and the British Museum embarked upon a joint expedition to the ancient site of Ur in southern Iraq.

Led by British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley, this expedition astonished the world by uncovering an extraordinary 4,500 year-old royal cemetery with more than 2,000 burials that detailed a remarkable ancient Mesopotamian civilization at the height of its glory.

Iraq’s Ancient Past:Rediscovering Ur’s Royal Cemetery

Sunday 25 October 2009, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology will open a new long-term exhibition, Iraq’s Ancient Past – which will bring many details of that famous expedition vividly to life through field notes, photographs and archival documents, and more than 220 extraordinary ancient artefacts unearthed at the excavation. The exhibition looks at the present and to the future as well, exploring the ongoing story of scientific inquiry, research and discovery made possible by those excavations, and the pressing issues around the preservation of Iraq’s cultural heritage today.

Centrepiece of the exhibition will be the collection of famous ancient artifacts uncovered and, in some cases, painstakingly conserved, including five objects that art critic and former Metropolitan Museum of Art Director Thomas Hoving has called “the finest, most resplendent and magical works of art in all of America”: the Ram-Caught-in-the-Thicket (visiting from London), the Great Lyre with a gold and lapis lazuli bull’s head, Queen Puabi’s jewellery, an electrum drinking tumbler, and a gold ostrich egg – as well as the royal’s headdress and other treasures, large and small.

The Excavations at Ur

Iraq’s Ancient Past recounts the formation of the joint Penn Museum/British Museum expedition to Ur, setting up the “expedition house” for the excavation team, and the many excavation challenges that Woolley’s team faced.

Known today as “Tell al Muquayyar,” or “mound of pitch (tar),” the site of Ur, near present-day Nasiriyah, was thought to be “Ur of the Chaldees”- the birthplace of the biblical patriarch Abraham. During these excavations, Woolley hoped to uncover Abraham’s home and other biblical evidence. In 1929, he interpreted a deep layer of river clay he uncovered to be the remains of a “great flood” from the biblical story of Noah. Like so much discovered at Ur, his sensational story made international headlines.

His major discovery, however, was the site of Ur’s royal cemetery. The Royal Cemetery of Ur excavations became one of the great technical achievements of Middle Eastern archaeology and now represents one of the most spectacular discoveries in ancient Mesopotamia.

With a crew of hundreds, Sir Woolley began this massive excavation in 1926, eventually uncovering nearly 2,000 burials. Sixteen of these he named “royal tombs” based on their style of construction, evidence of royal attendants who were interred at the same time, and the sheer wealth of the graves’ contents. The three most celebrated tombs were PG789, the looted tomb of a king, PG800 and the remarkably preserved tomb of Queen Puabi, and PG1237, which he dubbed “the Great Death Pit” since it contained 74 carefully laid out and richly adorned bodies, all but six female.

The Treasures Found in Queen Puabi’s Tomb

The tomb of a royal woman named Pu-abi was intact and its contents typical of the wealth found throughout the cemetery. Pu-abi’s body – identified by an inscribed cylinder seal found at her breast – lay on a wooden bier in the chamber.

Queen Pu-abi wore an elaborate headdress consisting of gold leaves, gold ribbons, strands of lapis lazuli and carnelian beads and a tall comb, along with chokers, necklaces, and large lunate-shaped earrings.

Pu-abi’s upper body was covered by strands of beads made of precious metals and semiprecious stones that stretched from her shoulders to her belt and ten rings decorated her fingers. A diadem or fillet made up of thousands of small lapis lazuli beads with gold pendants depicting plants and animals was apparently on a table near her head.

Two servants were found in the chamber with the Queen, one crouched near her head, the other at her feet.

As provided by Iraq’s first Antiquities Law, established in 1922, the artifacts were divided between the excavators and the host country. The artefacts currently housed in the British Museum, the Penn Museum, and the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

The famous excavations attracted the attention and involvement of a number of interesting personalities whom the exhibition also highlights. For example, Thomas Edward Lawrence – the ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ – was instrumental in securing the excavation and Woolley’s participation, while Agatha Christie wrote Murder in Mesopotamia to mark her experience on the dig site.

New Discoveries

Since the excavations came to a close in 1934, scholars have continued to study the Penn Museum’s Ur collection, incorporating new evidence from other ancient sites and using improved conservation practices and new scientific techniques to further investigate the material.

For example, because almost nothing excavated from the royal tombs could have been created from locally available materials, the exhibition details how scholars are rebuilding the story of 4,500-year-old trade networks across the Near and Middle East.

Similarly, conservation and research on individual artifacts has yielded new information about life at Ur – sometimes directly contradicting Woolley. When he found the bodies of dozens of funeral attendants in the Great Death Pit, each with a cup nearby, he proclaimed they had willingly imbibed poison to join their Queen in the afterlife!

New evidence from CT scans performed at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania reveal another story.

Iraq’s Ancient Cultural Heritage at Risk

The exhibition concludes with a look at the situation in Iraq today, where looting in the Iraq National Museum (opened in 1924 with objects from the Ur excavations) and at archaeological sites throughout the country has destroyed much evidence about the past. More than 30 years ago, then-president Saddam Hussein built the Iraqi airbase of Tallil next to Ur. To date, the Ur excavation site has been largely preserved, having been contained within the boundaries of air base and under the control of allied forces until May 2009 when the site was officially returned to Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities in a grand ceremony staged at the footstep of Urs most famous monument, the partially restored 4,100 year old Ziggurat.

‘Iraq’s Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur’s Royal Cemetery’ opens October 25th, 2009 at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Museum hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 10am to 4:30pm, Sunday 1pm to 5pm. Closed Mondays and holidays. Admission donation is $10 for adults; $7 for senior citizens (65 and above); $6 children (6 to 17) and full-time students with ID; free to Members, Penncard holders, and children five and younger; “pay-what-you-want” after 3:30pm daily. Penn Museum can be found on the web at www.penn.museum.

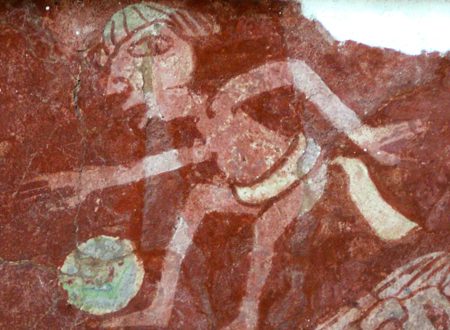

All Images Courtesy the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.