Dr Michel Baud of the Louvre Museum in Paris gave an interesting lecture last week about his excavations of a pyramid at Abu Roash. The monument was badly preserved and its stone had been quarried in Roman times, but the certain details, such as its apparent solar connections, were still discernable. Earlier, Vassil Dobrev stated that the pyramid may actually be a solar temple. However, Baud dismisses these claims….

Dr Michel Baud of the Louvre Museum in Paris gave an interesting lecture last week about his excavations of a pyramid at Abu Roash. The monument was badly preserved and its stone had been quarried in Roman times, but the certain details, such as its apparent solar connections, were still discernable. Earlier, Vassil Dobrev stated that the pyramid may actually be a solar temple. However, Baud dismisses these claims….

Nearly 4,500 years ago, in the time of the Old Kingdom, the pharaoh Khufu built one of the greatest monuments on earth – the Great Pyramid. His pyramid was actually a complex of monuments at Giza. Using up 2.7 million cubic meters of stone, it incorporated three queens pyramids, a satellite pyramid and hundreds of mastaba tombs for his officials. At a height of nearly 147 meters it was the tallest human-made monument in the world up until the construction of the Lincoln Cathedral in the 14th century AD.

So what did Khufus successor do? The person who succeeded him as pharaoh would have had a tough act to follow. We know that the person who succeeded him as pharaoh was a man called Djedefre (also spelled Radjedef). He was Khufus son and, like his father, would have had access to the vast resources of the Egyptian state.

His reign is estimated at 11 years and in that time we know that he built a pyramid complex at a place called Abu Roash. Sadly it has not stood the passage of time very well. During the Roman period (ca. 2000 years ago) the pyramid was quarried for its stone and, as such, there is little left standing today. The 20th century has also not been kind to this monument during the last century it was used as a military camp and its proximity to Cairo exposed it to modern development.

In recent years a Franco-Swiss expedition has been analyzing the remains of this pyramid and its nearby buildings. They have been at it since the 1990s and in that time have made quite a number of findings. One of the team members, Dr. Michel Baud, a curator at the Louvre Museum, gave a lecture at the Royal Ontario Museum last Thursday to discuss the latest research. I was at the talk and Dr. Baud granted an interview afterwards. He also generously released some photos of the site.

The Pyramid of Djedefre

At 103 meters in length, Djedefres pyramid at Abu Roash was a formidable monument, but nowhere near the size of Khufus. It was almost exactly the size of Menkaures, said Dr. Baud, referring to the smallest of the three pyramids on the Giza plateau.

Baud emphasized that there was nothing unusual in Djedefre choosing a site different from his father, Khufu.

Baud emphasized that there was nothing unusual in Djedefre choosing a site different from his father, Khufu.

The strange thing, I should say, is not Djedefres (pyramid), said Dr. Baud. The strange thing is definitely Khafre who chose to be buried very close to his father starting a sort of dynasty necropolis.

In fact, Baud said, contrary to popular belief, the pyramid of Djedefre is not an unusual structure at all. Excavation revealed that its a normal monument, he said.

The slope of the pyramid would have been between 50 and 52 degrees, an angle which is just about the same as the pyramid of Khufu. It also had a mortuary temple, boat pit, satellite pyramid, inner and outer enclosure walls. It also has a descending passageway that takes people down into the funerary chamber.

Unfinished Pyramid

The pyramids layout does contain two anomalies. The pyramids causeway, which would have connected the pyramid complex to a valley temple, trails off to the north rather than going south. There is probably a topographic reason for why it goes north, said Baud.

“We can say that in the reign of Djedefre there are strong solar connections”

The second anomaly, and the one tougher to explain, is the presence of what seems to be dwellings for priests beside the pyramid, along with storage areas. Usually this is something you expect in the valley temples, said Baud. Everything is on the plateau, it is quite strange.

Another misconception about this pyramid, that Baud tried to debunk, is that it was nowhere near completed when Djedefre died. There are such huge piles of granite that it of course means that this monument was at least half finished and probably more, said Baud.

The team also found solid evidence that construction of the pyramid began as soon as Djedefre became pharaoh. We also found in this descending cooridor the painted mark of the first year of Djedefre, said Baud.

Finally, as has been reported in the past, Abu Roashs natural elevation is higher than Gizas. This means that, although Djedefres pyramid is smaller the Khufus, topographically it is almost the same height. With lesser means he had the same level in the sky, said Baud.

Solar Temple, or Just a Solar Connection?

There is solid evidence that this pyramid had solar ties to it, said Baud. “We found a huge number of statue fragments all in quartzite, he said. We know in Egyptian beliefs this stone was associated with the sun.

Baud explained that purple is a colour associated with the rising sun and there is also some yellow on the fragments. This is probably why we can say that in the reign of Djedefre there are strong solar connections, he said.

Baud started reconstruction work of the statue remains in the 1990s and it is being carried on today by an Egyptologist in Belarus. There are about 1,100 fragments – its a complete nightmare”, he admitted.

This idea, that the pyramid has strong solar ties, has spurned one Egyptologist to suggest this monument was actually a sort of sun temple. Vassil Dobrev, of the French Institute of Archaeology in Cairo, made the suggestion in an interview with Newsweek two years back. Its not even a pyramid,Dobrev toldthe publication.

I asked Dr. Baud about Dobrev’s claims. He said that sun temples are known monuments… there is nothing like it at Abu Roash.

He added that, its a special funerary complex with solar connection but (to) go as far as to say it is a solar temple is something I cannot accept.

The Royal Cemetery

Royal cemeteries are features that were commonly built near pyramids.

Royal cemeteries are features that were commonly built near pyramids.

Ancient Egypt was a complex state and the pharaoh was served by numerous officials and courtiers. The offspring of the pharaoh also wanted to be buried near their fathers pyramid. Royal cemeteries, built close to pyramids, accommodated these people through mastaba tombs. Giza has hundreds of them.

Baud believes that his team has identified the royal cemetery used for Djedefres pyramid. It contains roughly 50 mastaba tombs and is located about 1.5 km east of the pyramid itself. Compared to the royal cemeteries at Giza this is a very small site.

Its nothing, Baud said when asked to compare this cemetery to Giza. Its a little Giza – but a very, very little Giza.

Giza Versus Abu Roash

The cemetery at Abu Roash was layed out in a disorganized fashion a throwback to the way royal cemeteries were set-up at pyramids before Khufu. This stands in contrast to Khufus cemetery which showed extreme order.

Dr. Baud also pointed out another discrepancy between the Khufu and Djedefre. There is something strange, by the way, with Khufus necropolis, he said. He built more mastabas than were needed, adding that some of them are unoccupied.

What we can see at Abu Roash is the opposite, clearly there are fewer mastabas but they are for somebody. Dr. Baud suggested that perhaps Khufus mastaba building project was pre-calculated, in some way.

Exploring the cemetery

The Abu Roash cemetery was excavated by an assortment of archaeologists in the early 20th century. Baud, in his efforts to study it, ran into two problems. The situation is really complex because we have a destroyed site first, then we have people who excavated there and left no records.

The Abu Roash cemetery was excavated by an assortment of archaeologists in the early 20th century. Baud, in his efforts to study it, ran into two problems. The situation is really complex because we have a destroyed site first, then we have people who excavated there and left no records.

He showed the audience a picture of the tombs, it looks more like a battlefield of the First World War in France than anything else, he said.

Bauds aim is to prove beyond doubt that this was a royal cemetery connected with the Djedefre pyramid.

He made a trip to the basement of the French Archaeological Institute where he found poorly recorded remains from the early 20th century digs. Some were defined as Old Kingdom site question mark. There were hundreds of boxes full of artefacts and architectural remains.

Not all the artefacts from Abu Roash are in the basement, some are in the Louvre or in other museums. Baud also went through photographic archives, including some stereoscopic photographs.

One inscription he studied refers to a man named Nykau-Radjedef. He appears to have been a son of Djedefre. The inscription reads.

The sole friend of his father, director of the ah-palace

A bit of caution has to be added to this interpretation since the title of kings son could be given as a reward to a high official. However, there are a number of kings sons at this cemetery, enough that it seem difficult to imagine this not being a royal cemetery. Also the title, director of the ah-palace, was not given at this time to (just) anybody, said Baud, suggesting that this person was Djedefres biological son.

A bit of caution has to be added to this interpretation since the title of kings son could be given as a reward to a high official. However, there are a number of kings sons at this cemetery, enough that it seem difficult to imagine this not being a royal cemetery. Also the title, director of the ah-palace, was not given at this time to (just) anybody, said Baud, suggesting that this person was Djedefres biological son.

Another clue that Baud found in the basement was a fragment from an alabaster offering table dedicated to a person named Hornit who is identified as the kings eldest son. Again another caveat needs to be thrown in. The title of eldest doesnt necessarily mean that he is the kings oldest biological son. Eldest can also be a title given to someone to signify their importance, still, because hes a member of the group of the eldest, hes someone very important, said Baud. The alabaster fragment was found in a mastaba (F13) that is about50 meters long, one of the biggest at Abu Roash. A tomb fit for a royal prince.

Another Mastaba, F37, also belonged to an unnamed king’s son. It to is a prominent monument, about 50 meters long,on the southern end of Abu Roash. it was excavated by Charles Kuentz in the early 20th century.

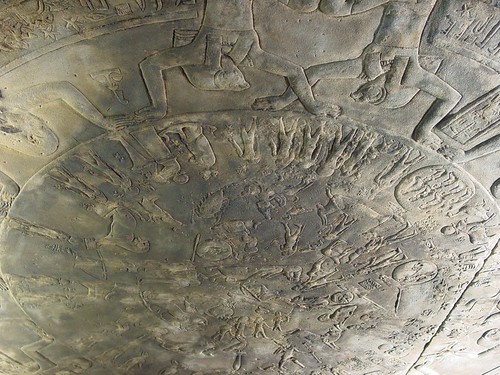

The Franco-Swiss team also did some digging, exploringMastaba F48. It occupies one of the highest places in the cemetery. This mastaba, although largely destroyed, yielded the remains of a chapel. It belonged to a director of the personnel in phyl,” and a picture of the tombs unnamed owner was found there. Dr. Baud released a photo of the find which is shown beside this article.

Dr Michel Baud of the Louvre Museum in Paris gave an interesting lecture last week about his excavations of a pyramid at

Dr Michel Baud of the Louvre Museum in Paris gave an interesting lecture last week about his excavations of a pyramid at  Baud emphasized that there was nothing unusual in Djedefre choosing a site different from his father, Khufu.

Baud emphasized that there was nothing unusual in Djedefre choosing a site different from his father, Khufu. Royal cemeteries are features that were commonly built near pyramids.

Royal cemeteries are features that were commonly built near pyramids. The Abu Roash cemetery was excavated by an assortment of archaeologists in the early 20th century. Baud, in his efforts to study it, ran into two problems. The situation is really complex because we have a destroyed site first, then we have people who excavated there and left no records.

The Abu Roash cemetery was excavated by an assortment of archaeologists in the early 20th century. Baud, in his efforts to study it, ran into two problems. The situation is really complex because we have a destroyed site first, then we have people who excavated there and left no records. A bit of caution has to be added to this interpretation since the title of kings son could be given as a reward to a high official. However, there are a number of kings sons at this cemetery, enough that it seem difficult to imagine this not being a royal cemetery. Also the title, director of the ah-palace, was not given at this time to (just) anybody, said Baud, suggesting that this person was Djedefres biological son.

A bit of caution has to be added to this interpretation since the title of kings son could be given as a reward to a high official. However, there are a number of kings sons at this cemetery, enough that it seem difficult to imagine this not being a royal cemetery. Also the title, director of the ah-palace, was not given at this time to (just) anybody, said Baud, suggesting that this person was Djedefres biological son. A large new church, monastic burials and a vaulted room filled with Coptic wall paintings – new excavation work at the Monastery of Saint Apollo at

A large new church, monastic burials and a vaulted room filled with Coptic wall paintings – new excavation work at the Monastery of Saint Apollo at  The monastery flourished until the 8th/9th century AD and then declined. Boutros said that the new excavations show no sign of vandalism or destruction of the monastery. Instead it appears to have become abandoned over time.

The monastery flourished until the 8th/9th century AD and then declined. Boutros said that the new excavations show no sign of vandalism or destruction of the monastery. Instead it appears to have become abandoned over time.

When I asked Dr. Boutros where the team discovered art, he responded with one word everywhere.

When I asked Dr. Boutros where the team discovered art, he responded with one word everywhere.

It doesn’t happen all that often that the battle over ‘mere tomb paintings’ makes headline news – why would they, when they have the highly debated return of the Elgin Marbles to the Acropolis Museum to write about? But the whole world was shocked last week,

It doesn’t happen all that often that the battle over ‘mere tomb paintings’ makes headline news – why would they, when they have the highly debated return of the Elgin Marbles to the Acropolis Museum to write about? But the whole world was shocked last week,