Gustave Flaubert – the author of ‘Madame Bovary’ – travelled through Egypt from October 1849 to July 1850. Together with his friend and photographer Maxime Du Camp he journeyed from Alexandria in the North to Sudan in the South and back. This journey is the focus of the exhibition ‘Het Egypte van Gustave Flaubert’ (Gustave Flaubert’s Egypt), which runs at the RMO in Holland until April 4th 2010. The expo follows the famous French writer on his journey through Egypt and takes its visitors from the amazing pyramids at Giza and the sanctuaries at Luxor to the gigantic pharaonic statues at Abu Simbel in the deep south. Through fragments from Flaubert’s letters and diary, unique photographs by Du Camp and about a hundred ancient Egyptian artefacts the exhibition recreates a typical view of Egypt at that time, as seen through the eyes of a European traveller.

Gustave Flaubert – the author of ‘Madame Bovary’ – travelled through Egypt from October 1849 to July 1850. Together with his friend and photographer Maxime Du Camp he journeyed from Alexandria in the North to Sudan in the South and back. This journey is the focus of the exhibition ‘Het Egypte van Gustave Flaubert’ (Gustave Flaubert’s Egypt), which runs at the RMO in Holland until April 4th 2010. The expo follows the famous French writer on his journey through Egypt and takes its visitors from the amazing pyramids at Giza and the sanctuaries at Luxor to the gigantic pharaonic statues at Abu Simbel in the deep south. Through fragments from Flaubert’s letters and diary, unique photographs by Du Camp and about a hundred ancient Egyptian artefacts the exhibition recreates a typical view of Egypt at that time, as seen through the eyes of a European traveller.

Gustave Flaubert‘s travel diary – published as ‘Flaubert in Egypt‘ – gives a detailed account of his journey through Egypt. His travelling companion Du Camp took many exquisite photographs of the monuments and excavations they visited together, at that time not yet crowded with tourists and still partly hidden under the sand. Thirty-five of these pictures, amongst which some original calotypes, can be seen marvelled at in the exhibition. The combination of Flaubert’s very personal writings and the distant, professional photography of Du Camp creates an exotic view of 19th century Egypt.

But even without Flaubert’s words, Maxime Du Camp’s astonishing photographs speak for themselves, evoking romantic thoughts of an Egypt without – or with not to many – tourists, a desolated frame that presents the ruins of Ancient Egypt splendidly. I’m at risk of repeating myself, but being a ‘holidaymaker’ in the 19th century seems that much more magical than doing ‘all inclusive’ in the 21th. Or am being a bit to unrealistic? Let’s see, Flaubert complained about – in no particular order – stubborn donkeys, hungry hyenas, boredom and depression in Philae, fever and bad cheese. Not to mention that the local bird population was using the Sphinx as well as Cheop’s Pyramid as the public toilet.

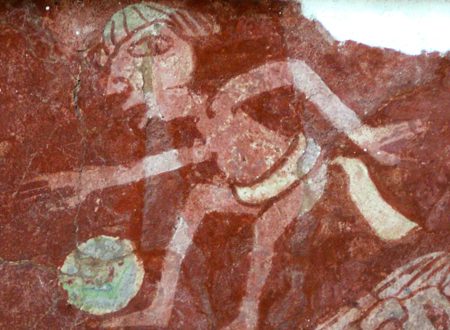

Besides the diary fragments and Du Camp’s photographs, Gustave Flaubert’s journey (overall a quite satisfying journey, don’t let the typical tourist complaints above mislead you) is illustrated at the RMO with over a hundred ancient Egyptian objects, including a sarcophagus of a priestess, crocodile mummies, papyri and two sphinxes. These valuable objects – on loan from different museums, and all related to or from the monuments and excavations the duo visited – give the public an idea of the archaeological splendour that these 19th century travellers encountered.

Although Ihardly dare to quote Flaubert’s impressions of the Sphinx (the Frenchman’s reasoning why the Sphinx must have been an Ethiopian king would be considered very ‘not done’ nowadays), here are his words on the Colossi of Memnon.

On May 2nd 1850, Gustave Flaubert wrote, “the Colossi of Memnon might be giant, but they are far from impressive. Very different from the Sphinx! The Greek inscriptions are clearly visible, it was so easy to discover them. Beholding the rocks that have fascinated so many people, visited by that many, does give a certain pleasure. How many bourgeois did not raise their eye at these? Each voiced their opinion on these, and then continued their own path.“

Personally, what I find the most refreshing about a ‘travelogue’ from the 19th century, is that – for once – it’s not all about King Tut. 😉

The RMOhas extended ‘Gustave Flaubert’s Egypt’ onto the internet; on the exhibition’s website you can read a selection of Flaubert’s diary fragments (in Dutch) and Du Camp’s magnificent photos whilst tracking Flaubert’s journey which is plotted on Google Maps, as well as voting for your favourite picture.

‘Het Egypt van Gustave Flaubert’ – curated by Dr Christian Greco and Dr Esther Holwerda – runs until April 4th 2010 at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, The Netherlands. Admission is included in the museum entrance fee, which is 9.