New research has shown that the symbols used by the ancient Picts were an actual written language not symbology. The Picts lived in Scotland from AD 300-843, and were a society ruled by kings. Historians know of them through the artefacts they left behind and via the writings of the people whom they had contact with, such as the Romans. In AD 843 they became incorporated into the larger Kingdom of Alba.

New research has shown that the symbols used by the ancient Picts were an actual written language not symbology. The Picts lived in Scotland from AD 300-843, and were a society ruled by kings. Historians know of them through the artefacts they left behind and via the writings of the people whom they had contact with, such as the Romans. In AD 843 they became incorporated into the larger Kingdom of Alba.

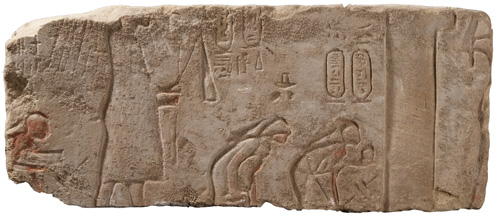

There are only a few hundred surviving Pictish stones. Some of them have symbols carved onto them like a relief. Christian motifs, such as a cross, can also be seen ona numberof them.

Researchers have long grappled with the question of what they represent. Are theymere symbols? Or are they full-fledged texts (albeit un-deciphered) which communicate a written language?

This kind of debate is common among scholars trying to unravel ancient symbols. The Indus Valley Script, used in the South Asia 4,000 years ago, is another example of an un-deciphered script that could be either symbols or language, and it was recently proposed that eggshells discovered in Africa could also demonstrate an unknown early language.

Is There Order in the Chaos of Symbols?

A team of language experts, led by Professor Rob Lee of Exeter University, used a system of analysis that looks at how random the symbols are.

If symbols are being written willy nilly, with little in the way of order, than its unlikely that they can be a written language. Imagine a writing systemwhere there are no rules how could anyone hope to communicate information?

On the other hand if there is order to the symbols, if things are being written in the same way over and over again, then there is a good chance that it does communicate written language.

Measuring the amount of randomness in an un-deciphered script is tricky because thereare usuallya limited number of examples (only a few hundred for the Pictish language) and quite often these havent been compiled together and published. This means that researchers have to work with small datasets, making this analysis tricky.

Next Step: Crack the Code

Working with the symbols available to them, the team was able to determine that there is some predictability in the Pictish symbols, enough so that it seems likely to be a written script. It is extremely unlikely that the observed values for the Pictish stones would occur by chance, the researchers said in a paper published recently in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society.

The next step is to expand their dataset and get a record of every Pictish symbol ever recorded. Researchers can then hone in on the language and, hopefully, decipher it.

Demonstrating that the Pictish symbols are writing, with the symbols probably corresponding to words, opens a unique line of further research for historians and linguists investigating the Picts and how they viewed themselves, said the team.

What we need now of course is a Scottish version of the Rosetta Stone or the Behistun Inscriptions to help researchers decipher the language. If the Pictish code can be cracked, we could be about to learn a lot more about the ancient people of Scotland, and open up our understanding of ancient Britain.