Like any major western city, modern London encourages its residents to live a lifestyle focussed upon the secular. On the surface, finance, business, fashion, the career and socialising outwardly seem to be the major concerns of Londoners as they rush around town. However, one does not need to look far to be reminded of the fact London is very much a religious centre, on top of being the hub for so many other preoccupations of British lives.

St. Paul’s Cathedral has been dominant in the city skyline, in one form or another, for nearly a thousand years. Westminster Cathedral and Westminster Abbey both dwell within the city centre, as do literally hundreds of other churches from many offshoots of Christianity.

In contemporary multicultural London we also find the largest Sikh and Hindu temples outside of India, the UK’s primary mosque and places of worship of every other sort, even Shaolin. The sacred sits alongside the temples of finance and commerce, much the same can be said for Roman London (find out all about ‘Londinium’ in this video).

In 1954 a major Roman temple dating back to the third century was discovered in the heart of London’s financial district, the temple belonged to a cult which had spread from as far east as India, all the way west to London and Spain. This set of beliefs had many parallels to what we recognise as Christianity today, and some say this cult, known as Mithraism, heavily influenced the formation of Christianity.

Who was Mithras?

Mithras, or Mithra, is thought to have been the most important god from an Iranian religion first recorded in the sixth century BC, in an era before Zoroastrianism. He was god of many things, the god of contracts and law to whom oaths were sworn; a deity who stood for loyalty to the ruler; the god of good relations between men and thus peace; god of the sun and source of light; he was the God of warriors and so also war; and also a deity who provided justice and demanded it from the actions his devotees. Mithras, in human form, fought and killed a mythical bull, an embodiment of the moon god Soma, which was then sacrificed. The Sacrifice of Soma and shedding of his potent blood brought light to the world and made life possible for mankind.

The Iranian form of the Mithraic religion slowly died over the centuries of Achaemenid imperial hegemony as the emperors’ Zoroastrian faith whittled away and then swallowed-up the followers of Mithras. On the western fringes of the Persian empire however, the Mithraic cult lived on, although it never spread to Greece, which is unsurprising given the Greek animosity to all things Persian. It may have reached Rome at some point, as from 136AD onwards archaeological records begin to record a resurgence in the religion as attested to by the discovery of inscriptions and dedications to the god Mithras. Over generations, much as with Christianity, ownership of this religion from a far off eastern land shifted and it became recognised as Roman. It is a subject of debate amongst historians as to whether the Roman Mithraism was truly born of its Iranian counterpart or can be considered to have a separate identity. The Mithras seen as a bearded figure, set against bright light emanating from behind his head, on Persian relief sculpture morphed into the idealised and cloaked man, with a Phrygian cap on his youthful face, as seen in Hellenistic Roman sculpture. This Mithras appears most commonly astride the bull as he seemingly effortlessly plunges his dagger home in sacrifice at the moment known as the Mithraic epiphany.

Why Did Mithraism Spread so Far?

Given Mithraism’s veneration of loyalty to authority, civil order and the warrior, it is unsurprising that the emperors had no complaints about the growth of this cult and some, such as Diocletian and Lucius adopted it themselves. Combine this reverence for worldly authority and bravery with Mithras’ status as a God of warriors, forged in the ilk of the masculine, Greco-Roman, beast killing heroes such as Hercules and we can see why Mithraism appealed to soldiers in particular. Roman soldiers were likely to find themselves posted right across the empire and so, as they took the adoration of Mithras with them, the religion spread virally to the outer reaches of Roman dominion. Indeed many of the Mithraic dedications and representations known to archaeologists were found on the extremities of the Roman empire, where soldiers were most abundant, with fewer found in peaceful provinces.

No better example of this can be found than the ruined Mithraeum at the Carrawburgh garrison next to Hadrian’s Wall, the wall built right across modern England which served in Roman times as the frontier at the North-Western edge of the Roman Empire.

Mithraism retained favour amongst emperors until the conversion of Constantine in the early fourth century AD, but prior to that it had comfortably fit into the prevailing religious shift towards monotheism and away from pantheistic religions. Looking back now, it could perhaps have been Mithraism which grew to become the world’s largest religion, had history deviated just a little at this point.

Watch the Ancient World in London Video – Londinium, Basilica Forum, Walbrook and the Temple of Mithras

In the second part of their adventure across Roman London, Ian Smith takes Nicole Favish to the centre of the city to Cornhill. Taking a trip to the basilica forum and St Stephen Walbrook, Ian explains how the Londinium forum was akin to the city centre such as modern day’s Oxford Street and Leicester Square. They attempt to visit the Temple of Mithras but it is currently in the process of being moved.

Ian discusses the importance of the River Walbrook to the development of Londinium in ancient times, before the pair go to the London Guildhall, and see the original site of the Roman Amphitheatre.

Where was the London Mithraeum?

Fast-forward to 1954AD, where workers are excavating the proposed site of the Bucklersbury House skyscraper, on Walbrook Street, in London’s ‘square mile’ financial district, better known as ‘The City’. Inadvertently, they unearth perhaps the capitals greatest Roman treasure. A Mithraic Sanctuary, including many of the original sculptures.

Sanctuaries to Mithras were built into the ground, to mimic the cave in which Mithras killed the cosmic bull, and by spilling this blood life was given and the world made fertile. The subterranean temples created an environment of darkness into which light was cast as if by the presence of the light god alone.

If we imagine descending into London’s Mithraeum, perhaps we would find ourselves amongst other followers masked or dressed in the appropriate masks according to their standing in the cult. Through the flickering candlelight frescoes and reliefs would be visible on the walls depicting Mithras, along with representations of other deities favoured by soldiers. Statues to Minerva, Mercury and Serapis gaze down, sculpted of such fine quality that they must have been imported from Italy. They are placed alongside less artful representations of Venus, combing her long hair. Kneeling or prostrating themselves in worship, the devotees are positioned around a central aisle, at one end of which is the centrepiece of the temple, a relief commemorating the moment Mithras delivered the sacrificial blow into the bulls side. On special ritual occasions perhaps you might see a live bull dragged noisily in, to be sacrificed within the temple. This would followed by a ceremonial meal where initiates ate together as Mithras did with the Sun God after he had killed the beast.

After ascending the stairs to leave the underground temple, with its impressive ground level faade, worshippers would find themselves within the Roman wall and surrounded by the hustle and bustle of Roman London, with its 60,000-plus residents, barracks of soldiers and traders from around the empire. Next to the Mithraeum runs the River Walbrook, which has since been covered over. Later on, the temple was rededicated to Bacchus and the divine statues of the Mithraeum were buried carefully within the site, where they were to remain for centuries.

After ascending the stairs to leave the underground temple, with its impressive ground level faade, worshippers would find themselves within the Roman wall and surrounded by the hustle and bustle of Roman London, with its 60,000-plus residents, barracks of soldiers and traders from around the empire. Next to the Mithraeum runs the River Walbrook, which has since been covered over. Later on, the temple was rededicated to Bacchus and the divine statues of the Mithraeum were buried carefully within the site, where they were to remain for centuries.

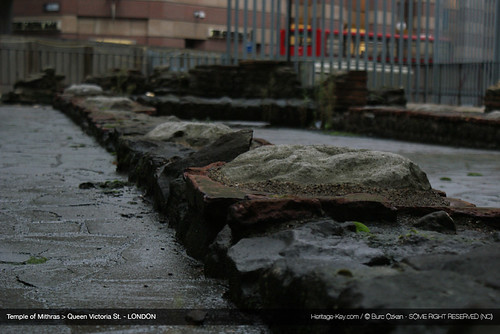

Today the site can still be visited, although what is left the temple sits above the ground, and is currently not on its original site, but at Temple Court on Queen Victoria Street. It is, however, to be moved back to the original Mithraeum location later this year. The statues found buried at the site of the Temple of Mithras are now on display in the Museum of London, where they have been placed amongst the atmospheric Roman Britain gallery.

What Form Did the Worship of Mithras Take?

Mithraism had a very masculine appeal in its imagery and belief system, which is reflected by the fact that it excluded women from membership. Like other secret society religions or cults, it required initiation ceremonies, seven in total, which protected deeper knowledge or secrets, and lured worshippers into greater dedication.

We do not know what forms the initiation ceremonies took, though it is thought simulations of death and resurrection took place, as well as tests of physical strength in ceremonial combat.

The number seven, significant in many different religious contexts, was also of importance to the Mithraist devotees. This was the number of stages to which initiates could attain membership. Namely: Corax (the Raven), Nymphus (the bridegroom), Miles (the soldier), Leo (the lion), Perses (the Persian), Heliodromus (courier of the sun), pater (the father). Each of the ranks had a corresponding mask to wear in ceremonies, excluding the bridegroom, who wore special items of clothing. The seven ranks were set against the seven steps on a ladder which were climbed and seven gates through which initiates had to pass.

What are the Similarities Between Mithras and Christ?

The parallels between Mithras and Jesus Christ warrant discussion. Without making any suggestions of religious plagiarism, there is at the very least much common ground, such as:

- A form of liquid baptism marks entry into both beliefs, although for Mithras it was blood rather than water.

- Some Mithraists are said to have believed their god’s virgin birth, though other sources state he was born from the earth itself.

They have a shared supposed birthday, on the 25th of December, followed by a visit from wise men on the 6th of January.

They have a shared supposed birthday, on the 25th of December, followed by a visit from wise men on the 6th of January.- Both are gods of light and truth, called King of Kings by their followers.

- Both are creator gods and both brought redemption through blood sacrifice.

- Mithras and Christ both took part in symbolically important meals where bread and wine were shared and consumed.

- They each lived celibate lives.

- Both gods were commemorated on Sundays.

- Each of the two ended their worldly existence by an ascension into heaven.

Intriguingly Mithraism’s holiest site, thought to be the cave where Mithras defeated the bull, just happens to share its location with the Vatican basilica; the hierarchy of Mithraism ordained that the highest positioned initiates were to be called ‘Pater’- father.

Because they were subterranean or built in caves, many Mithraea have been much better preserved than their above-ground counterparts. This must also be true for London’s Mithraeum.

It is fantastic for the British capital that the Temple of Mithras was preserved and discovered, and right that it should be on view to the public. The Mithraeum is a physical representation of the capital’s Roman history to be valued as much as the remains of the Roman wall. It was Roman planning and engineering, backed by the presence of the Roman soldiers, which the Mithraeum represents more than anything. This is what started London’s growth, and which culminated in the great capital and world city, with all the resultant heritage, that London is today.