Thomas Schneider is exploring a subject that has never been studied before. The University of British Columbia professor is examining the history of German Egyptology during the Nazi era. The period that lasted from when Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933 – until he committed suicide in his bunker in 1945.The research is a work in progress and Professor Schneider continues to receive new archival documents and information. He plans to turn his work into a book length manuscript.

While popular fiction, such as the Indiana Jones trilogy, depicts action packed films about this topic, the real story is far more complex.

Professor Schneider generously took the time to talk about his research with me. He also provided me with detailed written notes, that outline his research, to help me write this story.

Hitler Comes to Power

In January 1933, Adolf Hitler, head of the far-right National Socialist (Nazi) party, was sworn in as Chancellor. Over the next few years he and the Nazi party would gain control over Germany’s institutions and levers of power, allowing Hitler to govern as a de-facto tyrant.

One of those institutions was the universities which, before the rise of the Nazis, had enjoyed a level of autonomy. A tradition established in the 19th century saw the state as a “benevolent patron” for academic life. With Hitler in power, that quickly changed.

“Since its inception, National Socialism strove for implementing a new system of education in agreement with its doctrine across the country’s institutions of learning,” Professor Schneider wrote.

“This policy was meant to be applied in a particularly stringent way to the institutions of higher learning which were seen as the potential spearheads of the new nation but also feared for their intellectual independence and power.”

Photo from wikimedia, in public domain. Before the rise of the Nazis, Egypt was a respected centre of Egyptology. James Henry Breasted, pictured here, got his PhD from the University of Berlin.

Before Hitler’s rise to power Germany was a respected centre of Egyptology. The foreign affairs ministry financed an archaeological institute in Cairo that was used as a base to conduct scientific research.The country’s scholars had made important contributions. To name a few examples, Adolf Erman helped unravel the grammar of Egyptian writing.Ludwig Borchardt uncovered the bust of Nefertiti and Heinrich Schäfer broke new ground in the understanding of Egyptian art.

Professor Schneider pointed out that, in this pre-Nazi era, many American Egyptologists received their training in Germany, including James Henry Breasted (who, ironically, some regard as an inspiration for the Indiana Jones character).

A Changing Situation

Professor Schneider urged me to get an important point out in this story:

You need to “warn the public against believing the discipline during the Nazi period was uniform,” he said. “You’re dealing with a number of individuals, a number of professors,” he said, adding that the situation also changed depending on the year and the institution.

As I listened to the professor, and read his notes, I came to understand his viewpoint. The people involved in Egyptology, during this time, reacted to Nazism and its belief in the supremacy of an “Aryan race,” quite differently.

There is only a small cast of characters involved. Egyptology, in Nazi Germany, was a relatively small discipline. In 1945 there were only six chairs dedicated to the subject in the Reich with further positions as junior professors or museum staff. “The people they knew each other,” said Schneider.

Photo in public domain. Source United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. May 10, 1933, SA members and university students march in a torchlight procession around the bonfire of “un-German” books on the Opernplatz. In this environment Egyptology’s right to exist was questioned.

Egyptology ChallengedIn 1935, Helmut Berve, a professor of ancient history at the University of Leipzig and a dedicated Nazi, questioned Egyptology’s right to exist as a discipline. He wrote:

The study of the Ancient Near East as far as it relates to peoples of a foreign race, of a nature alien to us and thus impossible to comprehend fully in its peculiarity, is doomed to resignation as soon as the problems exceed what can be established rationally.

Therefore, it fails with regard to the new claim of values and losses its right to exist (…). Where the threshold of deeper questioning has been tred upon – as in Egyptology –, serious decisions have now to be taken.

He expected that.

Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Germany will automatically focus on the peoples akin to us in terms of race and mind; Egyptology and Assyriology will recede into the background.

Schneider writes, “Berve pleaded for a national history both committed to and committing German nationhood (‘volksverbunden und volksverbindlich’) and tied the possibility of historical understanding to race ideology.”

Photo by Andrea B. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic. Photo of a statue of Akhenaten, in the National Museum of Alexandra. Pro-Nazi Egyptologists Walther Wolf and Hermann Kees, despised the Amarna pharaoh. Kees wrote that he, “possessed too many traits that were contrary to the Ancient Egyptian ideal of a master race.”

Pharaoh as FuhrerWalther Wolf was an Egyptologist at Leipzig who had pro-Nazi leanings.

He is known for lecturing while wearing a SA uniform. The SA was a pro-Nazi organization that sprang up in the 1920’s. They were the main force in Hitler’s unsuccessful coup attempt in 1923.

In 1937 Wolf authored a defence of Egyptology as a discipline “Wesen und Wert der Ägyptologie.”

Professor Schneider writes that Wolf’s defence, “unveils the distinct will to align his discipline with the doctrinal requirements of the new ideology. It postulates for Ancient Egypt a predominant significance of the racial collective (“Volksgemeinschaft”) which Wolf believes to have been essential for the shaping of Egyptian culture (kulturprägend) and which he said was owed to “soil and blood” (Boden und Blut).”

Adding, “Wolf construes pharaoh as the realizer of forces lying dormant in the national collective and waiting to be set free.”

If these ideas sound familiar, they should, this leadership model for pharaoh is very similar to that which Hitler used for himself.

Wolf viewed Akhenaten to be a poor pharaoh because he ‘Did not uncover ideas that were lying dormant in the depth of their Volkstum, and fight for their full potential of development.’

“This is clearly worded on the template of the role assigned to Hitler,” wrote Schneider.

The Anti-Nazi League

As Wolf attempted to twist Ancient Egypt into something the Nazis could agree with, a prominent Egyptologist stood up against this. Alexander Scharff held an Egyptology chair at the University of Munich. He was strongly anti-Nazi and in 1938 authored a piece that dismissed Wolf’s attempt to see Egyptology through the lens of Nazism.

Said Scharff of Wolf’s work:

In it the attempt is made to understand the Egyptian culture from a new angle of view which is apparently rooted in National Socialistic ideology (…). Such slogans of today which may have a predominant significance in other areas, are of little use with regard to Ancient Egypt.

There is no question of “race” being a factor in the formation of Ancient Egypt (…). It seems to me that a political event, and be it of the scale of the German revolution of 1933, cannot at this moment transform our understanding of a past civilization to the extent the author would like to make us believe with his treatise which to all appearances is meant to be programmatic. Academic arguing has always proceeded with measured steps, without being tied to particular dates.

Professor Schneider told me that despite Scharff’s anti-Nazi leanings he managed to keep his job until the end of the war.

Photo in public domain. Source United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Goebbels speaks at a book burning in May 1933. His propaganda ministry would force George Steindorff out of his job and eventually, out of Germany.

Facing a Concentration CampGeorge Steindorff was a prominent Egyptology Professor at Leipzig. He was also Jewish. He edited the journal Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache and was in charge of other editorial projects.

In a 1935 letter to Adolf Erman, he lamented what was happening in Germany. He wrote-

The Nuremberg legislation has completely paralyzed us and cut our thread of life, it has annihilated our zest of life and my zest of work (…). I was always proud to be able to say “civis Germanus sum”, and cannot bear it to be locked up in a ghetto.

We are likely to spend the few years that fate grants us with wandering all over the world, deprived of our homeland. In the place where I worked honestly for more than 40 years and where I was conferred all honours, I don’t want to and cannot stay any longer.

No power of the world will (make) me take my pride; I don’t want to be pitied, rather I pity the other. But there is one thing I have learnt in these days (…): to hate.

Professor Schneider said that it appears as if the Ministry of Propaganda found it intolerable that a Jew have these editorial responsibilities and pressured Steindorff heavily to quit.

“There was a directive from Berlin that Steindorff could no longer be the protagonist of those publishing projects in Germany, those should go to a Nazi official.”

Steindorff was forced to quit the journal in 1937 and in 1939 left for the United States.

Walther Wolf, the SA uniform wearing Egyptologist mentioned earlier, was his replacement. Schneider believes it’s probable that Joseph Goebbels himself made the decision to force Steindorff out.

In 1938 Steindorff was in a desperate situation and was saved by an Egyptology colleague Dr. Hans Bonnet. Steindorff wrote in 1945, after he was safely in the United States that,

During my darkest days at Leipzig, some weeks after the pogrom of November, 1938, he came to our house in Leipzig and invited me and my wife to go with him and find asylum in his house at Bonn, though to give us sanctuary might well have resulted in his confinement in a concentration camp.

Photo by Chris P. Jobling. Creative Commons license Attribution Share Alike 2.0 generic. The bust of Nefertiti in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin. Hitler was a fan of this work and was going to place it in a new museum, in Berlin, near a bust of himself.

A Base in EgyptWhen the Nazis took over Germany they inherited the Cairo office of the German Archaeological Institute.

In other countries a special SS unit, the Ahnenerbe, was used to conduct archaeological research. Professor Schneider explained to me that the SS left Egypt alone and archaeological work was done by the institute`s Cairo office.

The Cairo office operated until the war started in 1939. During that time Professor Schneider believes that the Nazis used it as a base to advance their interests in the Middle East.

It was “a local outpost that could be instrumentalized for the government,” he told me. Germany had a number of interests in the area, including talking to Arab leaders who opposed Jewish settlement in Israel.

The head of the institute, after the Nazis came to power, was Hermann Junker. He was an established Egyptologist. During the time of Nazi rule he conducted digs in the Cairo-Memphis area and Nubia. But, he spent the bulk of his energy excavating at the Great Pyramids at Giza.

He was, “deeply involved in national socialism and a member of the NSDAP and other Nazi organizations during the war,” said Schneider.

I asked Professor Schneider whether the Nazis got involved in his fieldwork, directing him to excavate at the Great Pyramids or telling him to look for certain artefacts. Schneider said that he has found no evidence of that kind of control. He believes that, when it came to excavations, Hitler’s government let Junker pursue his own agenda.

The details on what the institute was being used for are still being researched. But there is evidence that is was used for more than archaeology.

In June 1945 George Steindorff, now living in the United States, wrote a letter to John Wilson, a professor at the Oriental Institute in Chicago. In the letter he discussed the involvement of different German Egyptologists with Nazism.

He wrote about Junker that,

It is very difficult to describe the character of this man because he has none. I have heard that it was rumored in England that Junker acted as a spy in Egypt. I do not believe it. He was too clever to compromise himself by such activity. He played safe.

However, he used his position and the State Institute to promote Nazi propaganda. The Institute was always available for Nazi meetings, Junker’s house was always open to Nazi guests, chiefly Austrian. Every Nazi found a cordial reception in the German Institute in Cairo. I appreciate Junker as a scholar of the first order. More than that, I am sorry I cannot say. At best, his actions and opinions have always been ambiguous.

Photo by Daniel Schwen, posted on wikimedia. Creative Commons attribution share alike 2.5 generic. Great Hall at Göttingen University.

The Göttingen ManifestoHermann Kees was a professor of Egyptology at the University of Göttingen. According to Schneider’s research he was president of an extreme right-wing group Deutschnationale Volkspartei and played an indirect role in driving Albert Einstein out of Germany.

He was, “instrumental in the expulsion of Jewish faculty in 1934, after the laws for the restitution of the Civil Order were put into force,” Schneider wrote.

In 1934, after the death of German president Paul von Hindenberg, Hitler implemented a series of laws that barred Jews, and people opposed to Nazism, from serving in government positions.

Albert Einstein (then based in Berlin) and his colleage at Göttingen, Nobel Laureate James Frankh, both resigned in protest. They were hoping that other professors would resign in solidarity.

That didn’t happen.

Fourty-two professors at Göttingen published a manifesto condemning Frankh’s resignation and calling for a faster implementation of the “necessary measures of purging.”

“This happened fast,” wrote Schneider. “One day after the publication of the manifesto, the first six Jewish professors were relieved of their duties. The man who initiated the manifesto and the expulsion of Jewish faculty was Hermann Kees.”

Einstein’s and Frankh’s hope had failed at Göttingen.

Kees certainly didn’t hide his far-right views. On Akhenaten he wrote,

One is certainly wrong to portray Amenophis IV as a gushing idealist who wished to turn the world’s quarrels to eternal peace by the gracious sermon of human reconciliation and who therefore declined any warfare abroad.

To be a great reformer, he lacked the creative force to anticipate, in the way of a seer, issues that were fermenting and wanted to take shape, and to shape them, and not the least did his personality lack authoritative charisma, carrying the stigma of repulsive ugliness.

He himself possessed too many traits that were contrary to the Ancient Egyptian ideal of a master race; he was licentious, effusive, led by emotions, morally debauched and obstinate.

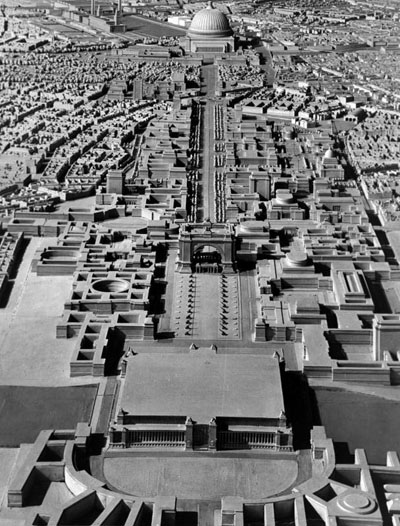

Courtesy German Federal Archive and wikimedia. Photo of a model of “Germania” Hitler’s revamped Berlin. It would have included a museum where Nefertiti’s bust was close to Hitler’s.

Hitler’s Own ViewsHitler’s own personal views on Egyptology remain something of a mystery. Professor Schneider said that more archival research needs to be done to determine this.

He does appear to have had an interest in Egyptian Art. Professor Schneider sent me an intriguing photo, dating to February 1939. It shows the opening of an Ancient Egyptian Art exhibition in Berlin. Sitting on the front row is Hitler himself.

Unfortunately I cannot post this photo on the web since the copyright is still valid and is held by a photography firm.

Schneider points out that Hitler was particularly interested in the bust of Nefertiti and vetoed its return to Cairo.

Hitler was planning to build a new museum in “Germania,” (his name for what would have been the transformed city of Berlin). According to Professor Schneider’s research the bust of Nefertiti would have been close to that of Hitler himself.

A Turning Point in Egyptology

It’s difficult to gauge the full impact that the events of 1933-1945 had on German Egyptology. But certainly the impact was negative.

“This was, what I think, a decisive turning point in the international history of Egyptology,” Said Professor Schneider.

“Germany lost its status and it has to struggle for many decades after the war until it again became recognized and appreciated (in) the discipline,” he said adding, “Germany had basically sacrificed, through the NS regime, its academic standing.”

“Germany had basically sacrificed, through the NS regime, its academic standing.”

The loss of people such as Steindorff, hindered the country’s knowledge base.

“They came not only from Egyptology but dozens of other disciplines, they established their fields of knowledge abroad, above all in the United States, and had they been given a perspective in a Germany without National Socialism they possibly would have stayed there. And many important strands of thinking or pools would have developed in Germany that now developed in the States,” said Professor Schneider.

“(The) people who stayed in Germany, or younger generations, as a direct consequence were different people than those who would have lived and had a career in (a) Germany without the Nazis,” he said.

“It is difficult to say how the discipline would look today without National Socialism but we can very certainly say that Germany would have a different standing today.”

The German Archaeological Institute in Cairo did eventually reopen after the way and today Germany is again a centre of Egyptological research.

Herman Kees and Walther Wolf were both removed from their positions after the war. Although in 1963 Wolf did get a professorship at the University of Münster. Kees notes were confiscated as part of de-nazification efforts something which hindered his writing efforts.

Years after the war Hermann Junker, while writing his memoirs, would choose to not write about the time of Nazi rule. Only saying that, “this was a dark time.”