Signs O’ The Times

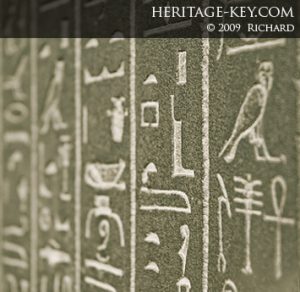

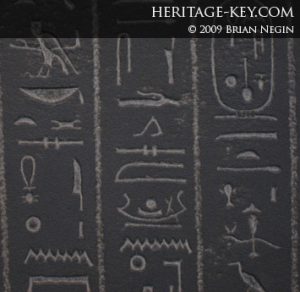

Egyptian hieroglyphs – streams of sometimes heavily stylised pictograms and letters, carved into stone or drawn onto papyrus parchment – are instantly recognisable relics of one of the world’s oldest and most famous ancient civilizations. But what on earth do they mean? And what of their place in the development of the Egyptian language, written and spoken, as a whole?

Origins and Development

Examples of written Egyptian date back more than 3,400 years, making it one of the earliest known languages in human history. The oldest bands of script discovered to date comprise a primitive system of labels and signs generally lumped together under the term Archaic Egyptian.

The last derivative proper of Egyptian prevalent in the region was Coptic. It was written using a modified version of the Greek alphabet and lasted from Roman times, circa 1 AD, until the early modern period, circa the 17th century, when it was snuffed out by the conquering Arabs, whose language is spoken in Egypt today (Coptic still reportedly has a handful of native speakers).

In the intervening centuries – from the Old (2600 BC-2000 BC), Middle (2000 BC-1300 BC) and Late (1300 BC-700 BC) Egyptian periods, through to the Demotic period (7th century BC-5th century AD), as categorised by language experts – history bears witness to the development of a formal writing system known as hieroglyphics, plus its less formal variations hieratic and demotic.

Hierowhatics?

The word hieroglyphics basically means “sacred carvings”, and is a Greek translation of the Egyptian phrase “god’s words”. The ancient Egyptians believed that writing was invented by the god Thoth – which may explain why it endured for so long, and why hieroglyphics only died out with the arrival of Christianity. The word came into use at the time of the early Greek contacts with Egypt, as a means of distinguishing the older hieroglyphics from the handwriting of the day (demotic).

Hieroglyphics have caused no shortage of head scratching amongst scholars over the centuries. One of the first known studies, the Hieroglyphica of Horapollo, written in the 5th century AD, was initially regarded as authoritative yet eventually proved totally false, after having actually impeded further interpretation for centuries. Arab historians Dhul-Nun al-Misri and Ibn Wahshiyya were the first to make real inroads, in the 9th and 10th centuries.

Western scholars have poured over hieroglyphs for centuries. It was the young Frenchman Jean-François Champollion who – thanks to the discovery in 1799 of the Rosetta Stone during Napoleon’s Egyptian invasion – made the biggest breakthrough. He established the similarity of Egyptian writing to ancient Greek, a masterstroke that meant later scholars were able to delineate the language into nouns, verbs, prepositions and other grammatical parts.

Not that it was simple or anything, as a letter written by Champollion to fellow intellectual André Dacier in the 1820s testifies: “It is a complex system, writing figurative, symbolic, and phonetic all at once, in the same text, the same phrase, I would almost say in the same word.”

Interpreting Glyphs

Champillion wasn’t joking. Visually, glyphs are more or less as literal as they appear, and represent directly the very things they depict – birds, fish, people or objects. But usually, hieroglyphs have semantic connotations too, or represent certain sounds or groups of sounds.

The glyph for a crocodile is a picture of a crocodile, but can also stand for the sound “msh”. A goose can mean a goose, yet also represent the same sound as the word for “son”. Scripts can run either from left to right or right to left, (unlike the cursive hieratic and demotic, which were only written from right to left). Fortunately, it’s easy to figure out which way to read – note which way the human or animal signs face, because they always look towards the starting point. That’s something at least.

Heavy Reading

Heavy Reading

There are many famous carved examples of carved hieroglyphics, such as the Narmer Palette – a shield shaped palette that dates to around 3200 BC, which has been described as “the first historical document in the world”. The Rosetta Stone, for its value as described above, is probably the best known hieroglyphic artefact of all. It’s a giant Ptolemaic era stele with carved text made up of three translations of a single passage describing a tax amnesty given to the temple priests of the day – two in Egyptian language scripts (hieroglyphic and demotic) and one in classical Greek. It was created in 196 BC, and has been exhibited almost continuously in the British Museum since 1802, despite Egypt’s passionate cries for repatriation of the artfact.

Many notable examples of hieroglyphics can be found written on Papyrus scrolls – thick sheets of paper-like material produced from the pith of the papyrus plant, which was once abundant in the Nile Delta. The Book of Dead – an ancient Egyptian funerary text describing the afterlife and giving guidance on how to endure it – was commonly written on a papyrus scroll and placed in the coffin or burial chamber of the deceased. They may not look it, but hieroglyphics were apparently essential reading for the ancient Egyptians even in death.