Some scholars consider the ancient Harappan pictograms of the Indus Valley in South Asia to be random. Not so, says Rajesh Rao of the University of Washington. He calculated the conditional entropy – a measure of randomness – of the script and found that it is most likely a language. Next, Rao will analyze the texts structure using simple statistical software.

Some scholars consider the ancient Harappan pictograms of the Indus Valley in South Asia to be random. Not so, says Rajesh Rao of the University of Washington. He calculated the conditional entropy – a measure of randomness – of the script and found that it is most likely a language. Next, Rao will analyze the texts structure using simple statistical software.

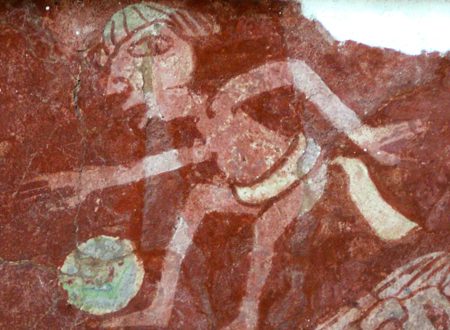

The ancient twin cities of the Indus Valley – Harappa and Mohenjo-daro – are part of one of the oldest civilizations known to man. They were huge metropolises holding over 30,000 people each. A series of symbols dating to around 2,500 BC has also been found in the area, yet historians are still unable to draw any meaning from them which could be construed as symbolic of an alphabet in the area.

Recent evidence suggests that the fertile Indus River basin could have been home to an empire larger and older than its more famous contemporaries in the Middle East, and thus be one of the cradles of civilisation. Up to now excavations in the Indus River Valley have provided us with roughly 5,000 seals, tablets and amulets, filled with about 500 different symbols, all created somewhere between 2600 and 1900 BC. But what do these tell us?

Despite numerous attempts to decipher the symbols – known as Harappan script – a full translation has long eluded scientists. Some archaeologists think to have found paralles with the cuneiform of Mesopotamia; others speculate an unlikely link between Harappan signs and the birdmen glyphs found thousands of miles away in the Pacific Ocean at Easter Island.

A 2004 paper even suggested that the Indus Valley people were functionally illiterate and the Harappan symbols were political or religious symbols rather than writing.

To start the search for what meaning the text might hold, American and Indian mathematicians and computer scientists input the symbols into a computer program and then ran a statistical analysis of the symbols and where they appear in the texts. Time.com explains:

The group examined hundreds of Harappan texts and tested their structure against other known languages using a computer program. Every language, they suggest, possesses what is known as “conditional entropy”: the degree of randomness in a given sequence. In English, for example, the letter “t” can be found preceding a whole variety of other letters, but instances of “tx” or “tz” are far more infrequent than “th” or “ta.” “A written language comes about through this mix of built-in rules and flexible variables,” says Mayank Vahia, an astrophysicist at the Tata Institute for Fundamental Research in Mumbai who worked on the study. Quantifying this principle through computer probability tests, they determined the Harappan script had a similar measure of conditional entropy to other writing systems, including English, Sanskrit and Sumerian. If it mathematically looked and acted like writing, they concluded, then surely it is writing.

This is just the beginning of ‘deciphering’ the Harappan symbols. The international team hopes to compose a grammar of Indus signs, as they’ve already found that certain placements of characters in the text to be more likely: a “fish” sign most frequently appeared in the middle of a sequence, a U-shaped “jar” sign toward the end.

This is just the beginning of ‘deciphering’ the Harappan symbols. The international team hopes to compose a grammar of Indus signs, as they’ve already found that certain placements of characters in the text to be more likely: a “fish” sign most frequently appeared in the middle of a sequence, a U-shaped “jar” sign toward the end.

There are some who say the Indus Valley script can never be deciphered without a bilingual text like the Rosetta Stone or really long texts, but Rao is optimistic that given a few more years, the team may be able to at least narrow down the language family of the script by using computer analysis to gain an in-depth understanding of the underlying grammar.

With the help of the software, Rajesh Rao, associate professor of computer science at the University of Washington imagines he could write in “flawless Harappan” – even though he may have no idea what the assembled sequences might mean.

Marcelo Montemurro, a scientist at the University of Manchester now wants to test the software on the up to know undecipherable medieval text known as the Voynich manuscript: “The text is not long, but these methods can be applied so we can at least obtain a list of special words that would presumably convey the overall meaning of the texts.”

With – amongst others – Proto-Elamite, Linear-A and Olmec still to go, the team won’t run out of Ancient Scripts to decipher anywhere soon! Luckily computing power gives modern-day scientists a huge advantage over their predecessors: not only for ‘breaking the code’ on mysterious ancient languages, but also in making documents thought long-time lost readable again.